Black History Month is the perfect time to remember the 1963 Kentucky Boys’ State High School Basketball Tournament because that’s the one that changed the sport forever and had an impact on society as a whole that many in the Commonwealth either didn’t notice or purposely ignored.

The tournament in Louisville’s Freedom Hall took place nine years after U.S. Supreme Court had rendered its historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling, ending segregation in public schools, transportation, and businesses.

The last all-white State Tournament in Kentucky took place in 1957. Later that year, in September, nine black students were blocked from integrating Little Rock Central High in Little Rock, Ark. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to escort the students from their homes through mobs of white hecklers.

In Kentucky, integration was moving smoother, and nowhere was it more obvious than in high school basketball. The field for the 1958 State Tournament including three black schools — Lexington Dunbar, Bowling Green High Street, and Covington Grant — along with Cynthiana High, whose best player, an African-American named Louis Stout, joined Dunbar’s Julius Berry and High Street’s Bobby Parrish on the all-tournament team.

In 1959, Dunbar finished third in the State Tournament and two years later it made the championship game on Saturday night, losing to powerful Ashland High 69-50, due mainly to circumstances that occurred in that morning’s semifinals.

I was a senior at Henry Clay High in 1961, and we had a good team, taking a 19-3 record into the 43rd District Tournament at the University of Kentucky’s Memorial Coliseum. We got by Bryan Station, 53-47, in the first round but then had to face Dunbar in the District semifinals.

The opening tip was between our Bill Brooks, a 6-foot-2 senior who was quick and could jump, and Dunbar’s 6-5 Henry Davis, who was chiseled and must have outweighed the skinny Brooks by at least 50 pounds.

Since we hadn’t played any black schools during the regular-season, I feared we were in for a drubbing. However, we did ourselves proud, losing by only 57-56 to a team that was destined to be the first black school to make it to the championship game of the Kentucky State High School Tournament.

Coached by S.T. Roach, who later became an important mentor and dear friend, the Bearcats were led by Davis and 6-3 guard Austin Dumas, an outstanding shooter. In the State Tournament semifinals, Dunbar played all-white Breathitt County from the mountains in the eastern part of the Commonwealth.

At the beginning, the predominantly white Coliseum crowd was overwhelmingly behind Breathitt County. But game officials Foster “Sid” Meade and Milford “Toodles” Wells were so blatantly biased against Dunbar that, at the end, almost everyone was rooting for the Bearcats, who won the game when Dumas hit a 61-footer just before the final horn.

That put Dunbar in the championship game against Ashland, which many still regard as the best high school team ever to play in Kentucky. Coached by by young Bob Wright, all five Ashland starters received NCAA scholarships.

Junior star Larry Conley went to UK, where he was the leader of the famed “Rupp’s Runts” team in 1965-’66. As for the four senior starters, Bob Hilton went to West Point, Gene Smith to Cincinnati, Steve Cram to Baylor, and Harold Sargent to Morehead State.

In the Saturday morning semifinal before Dunbar’s throbbing win over Breathitt County, the Tomcats breezed by Wheelwright, 91-80. Under the best of circumstances, Dunbar probably wasn’t good enough to beat Ashland. But they were so exhausted by the Breathitt County debacle that they really had no chance.

Oddly, the 1962 State Tournament was a hiccup in the civil-rights movement. The four semifinalists all were lily-white. No black player made the all-tournament team. That turned out to be segregation’s last hurrah in Kentucky high school basketball history.

Then, in 1963, came perhaps the most socially important state tournament in the commonwealth’s history.

The championship was won by a Louisville Seneca team that was built around Michael Redd and Westley Unseld, who still rank among Kentucky’s all-time greatest players, African-American or otherwise.

Redd, a 6-3 senior guard who was favorably compared with Michael Jordan years later, averaged more than 26 points as the Redskins (now Redhawks) stormed through the field at Freedom Hall. He benefitted enormously from the bulky 6-6 Unseld’s picks, rebounds, and outlet passes to trigger the fast break.

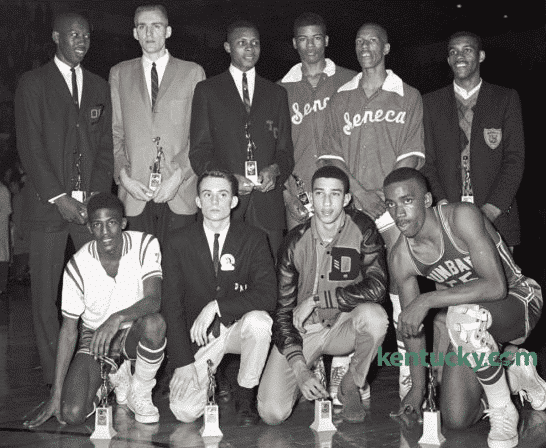

In the title game, Seneca defeated Lexington Dunbar, 72-66, in what turned out to be S.T. Roach’s last game as the school’s coach. Redd, the first African-American to win the coveted “Mr. Basketball” title, and Unseld were joined on the all-tournament team by Dunbar’s George Wilson and James Smith.

In fact, for the first time ever, black players dominated the all-tournament team. Of the 10 players selected, only Danny Shearer of Oldham County and Pearl Hicks of Clay County were white. The other blacks were Dwight Smith of Princeton Dotson, Charles Taylor of Owensboro, George Davis of Maysville, and Clem “The Gem” Haskins of Taylor County.

Working as a young reporter for The Lexington Leader, I took the photo of the all-tournament team that accompanies this column. I was pretty much oblivious to the racial importance because I had covered many of the players and considered them more as friends than pioneers.

Other milestones were coming. The next season, Unseld led Seneca to the title again, touching off a recruiting war between UK, still lily-white, and U of L, which had integrated its program in 1962. He picked U of L, where he became an All-American and then, in 1966-‘67, the first NBA player ever to be both Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player in the same season.

Then, in 1969, Louisville Central, led by Ron King and Otto Petty, became the first historically black school to win the state championship.

Another interesting point about 1963 is that the NCAA Final Four was held in Freedom Hall the week after the State Tournament. The title was won by Loyola of Chicago, the first college champion to have four black starters.

The civil-rights battle was far from over — it persists to this day — but 1963 was a good year for it. On Aug. 28, the Rev. Martin Luther King delivered his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech before a crowd of more than 200,000 on the Capitol Mall in Washington, D.C.

But then came Nov. 22, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. For Americans of all races, the world was never the same, and that goes for a baby born in Brooklyn on Feb. 17. His name was Michael Jordan.

(Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame and the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, among other honors. He’s covered sports for more than 40 years and is considered among the most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby. He’s the author of “Last of a BReed.” This column first ran in KyForward.)

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award three times. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades and is perhaps one of the most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby. His book “Last of a BReed” is available on Amazon.