A bill Kentucky hospitals say was essential to preserving funds for charity care appears dead after lawmakers in the House late Friday rolled Senate Bill 14 — plus several other health measures — into a single bill, effectively killing it.

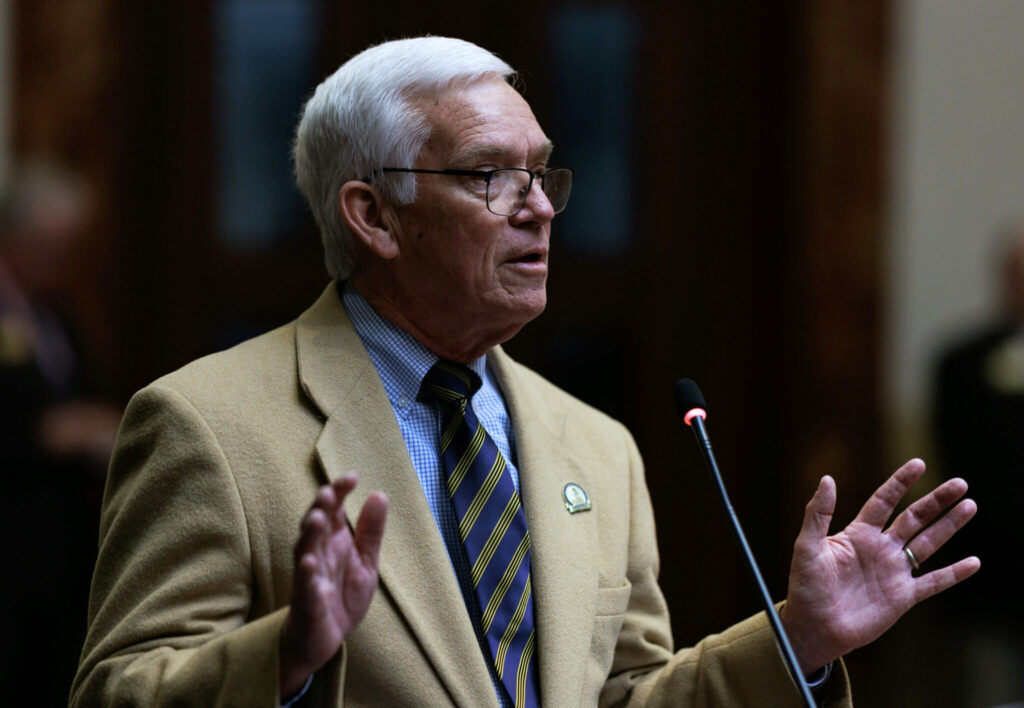

In announcing the demise of his SB 14 — meant to strengthen access to a federal program that raises money from pharmaceutical companies — an angry Sen. Stephen Meredith, R-Leitchfield, compared it to the Kenny Rogers’ song “Lucille.”

“I’ve seen some good times and I’ve seen some bad times, but this time the hurting won’t heal,” Meredith said in a Friday night speech on the Senate floor.

“It’s crushing to me,” he added, saying it puts funding from the 340B Drug Pricing Program for health care at risk throughout Kentucky. “This is not just a luxury, this is a lifeline, a financial lifeline for many of our communities.

The House action Friday also killed an unrelated bill sought by the state’s largest treatment program, Addiction Recovery Care, or ARC, to protect Medicaid payments for treatment services.

Senate Bill 153, sponsored by Sen. Craig Richardson, R-Hopkinsville, would have placed limits on how insurance companies that handle most of Kentucky’s Medicaid claims can restrict payments to providers they consider “outliers.”

But in a dizzying series of changes, the House deleted contents of SB 153, replacing it with Meredith’s SB 14, as well as several other measures, effectively killing them all. With only two days left in the session, it’s too late to revive them, sponsors say.

By turning SB 153 into Meredith’s SB 14 — among other changes —“in that moment, the bill was dead,” Richardson said in an email.

“It will be a fight for next session,” Richardson said.

Meredith said Richardson, a freshman lawmaker, afterwards expressed surprise at the outcome.

“I told him, ‘Welcome to the General Assembly,’” Meredith said.

‘Unworkable’ changes

Also included in the now-defunct bill was a measure by Rep. Kimberly Poore Moser, R-Taylor Mill, to create new, detailed reporting requirements for nonprofit hospitals and clinics on funds they receive through the 340B program.

Moser had argued at a committee hearing that such measures were needed to improve “transparency.”

Meredith said the reporting requirements were excessive and “just ridiculous.”

And the Kentucky Hospital Association, which had lobbied heavily for Meredith’s SB 14, said it could not support the newly-created version, describing the reporting requirements as “counterproductive.”

The changes “make the program unworkable, and Kentucky’s hospitals cannot embrace such legislation,” said a statement from a spokesperson.

Not everyone was disappointed.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, along with several other industry and employer groups, had opposed SB 14, arguing the 340B program has expanded too rapidly with little oversight and must be better managed. They argue 340B must be reformed by Congress, which created it in 1992 and has done little to check its growth.

It has devolved into a program in which hospitals and clinics get prescription drugs at steep discounts, and then, for insured patients, bill Medicaid and private insurance companies for the market price and pocket the difference, they said.

Calling it a “hospital markup program,” PhRMA spokesman Reid Porter said the discussion in Kentucky underscores the need for federal action.

“It must shift from a loophole benefiting tax-exempt hospitals at the expense of Kentuckians to a system that truly supports vulnerable patients and communities,” he said. “We appreciate the legislators who prioritized transparency and took steps to bring greater accountability to how 340B is used and we continue to support these changes at the federal level.”

ARC and the FBI

As for the original version of SB 153, it had drawn opposition from the Kentucky Association of Health Plans, or KAHP, which represents insurers and pointed out that ARC, one of the bill’s chief backers, is under investigation by the FBI for possible health care fraud.

SB 153 — meant to limit how private insurers known as managed care organizations, or MCOs, can withhold Medicaid payments they find questionable — would make it harder to act in such cases, it said in a March 12 news release prior to changes to SB 153 that killed it.

“The federal government is cracking down on waste, fraud and abuse,” Tom Stephens, KAHP CEO, said in the news release. “What kind of message does it send that Kentucky is doing the exact opposite.”

This week, Stephens welcomed the end of SB 153.

“We appreciate voices in the General Assembly arguing for real accountability,” Stephens said. “We have witnessed that a lack of guardrails has been a boon for disreputable providers and resulted in significant abuse of taxpayer dollars.

The FBI has not brought any charges in the investigation of ARC that it announced in August.

ARC has said it provides quality treatment services and is cooperating with the FBI.

‘The white flag’

Meredith, a former hospital CEO who was pushing his 340B bill for the second year, vowed he’s not giving up on legislation he said is needed to preserve health services, especially in rural areas where hospitals are struggling.

With potential Medicaid cuts looming at the federal level, Meredith said action is urgently needed.

“I guess I’ve got to wave the white flag on this one for this session but it will be back in 2026,” he said in Friday’s speech to fellow lawmakers. “I’m not just asking you for help on this, I’m begging you.”

In an interview, Meredith said the 340B program brings in about $250 million a year that hospitals and clinics, rural and urban, use to shore up charity care services. It doesn’t all have to go for direct care for patients who can’t pay, he said.

For example, one rural hospital uses proceeds to enhance nurses’ salaries to avoid losing them to larger hospital systems that pay more. Others use proceeds to enhance cancer care or other treatment they couldn’t otherwise afford.

“The program was never meant to provide charity care as much as it was to provide access to care,” he said.

Without his bill’s protection, pharmaceutical companies will continue to try to limit discounts and the type of drugs shipped to Kentucky, which will erode 340B funds, he said adding, “It just boggles my mind we’re willing to walk away from $250 million a year.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Deborah Yetter is an independent journalist who previously worked for 38 years for The Courier Journal, where she focused on child welfare and health and human services. She lives in Louisville and has a master's degree in journalism from Northwestern University and a bachelor's degree from the University of Louisville.