Gov. Andy Beshear spent much of his coronavirus update Monday talking about the importance of testing for the virus and tracing the contacts of people who have it — and then their contacts — to keep the virus in check as the state begins to reopen its economy.

“Contact tracing along with testing is absolutely critic for our reopening and for being healthy at work,” Beshear said, adding later, “It doesn’t work without you buying in, without your voluntary commitment to making sure that we are safe as we reopen.”

The concept is that increased testing will determine who actually has the virus, including many who are infectious but have no symptoms — about one in four, Health Commissioner Steven Stack, noting that studies vary.

Testing leads to contact tracing: tracking down people who have been in contact with an infected person, then asking them and their contacts to isolate for two weeks, the incubation period for the virus.

All this is called for by the guidelines the White House and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for reopening the economy, Beshear noted.

“So when we are talking about calling you and you picking up, this isn’t just me, this is the president, too,” he said. “This is Democrats and Republicans, federal government, state government, this is just public-health experts saying what’s got to happen for us to have a safe reopening and to restart our economy without pausing it.”

Beshear assured Kentuckians that any information provided through the tracing would be kept private. “Information provided is completely confidential, entirely,” he said. “And we will be looking at every privacy concern out there.”

He said contact tracing is not a new process, but something public-health agencies have long done to fight communicable diseases, in ways that also “require significant privacy and trust of Kentuckians. We can do this the same way.”

The state’s contact-tracing program will be led by Mark Carter, a certified public accountant with 40 years of experience in health care, most recently as CEO of Passport Health in Louisville, the state’s only nonprofit Medicaid managed-care company. He was widely mentioned as Beshear’s likely secretary of health and family services, but Eric Friedlander got that job last week after being acting secretary for five months.

Carter showed a video about contact tracing and said, “So we have to reopen the economy, but we also have to protect our children and our families, our friends from another outbreak of COVID. One of the key ways to do that, in addition to effective and expanded testing that has been accomplished, is through the contact tracing program. … I’ve always been an optimist, and I know we can have it both ways. It’s not a binary choice between reopening the economy and protecting people’s health. We can do both, but we need to do it together.”

Health Commissioner Steven Stack stressed that the effort will require Kentuckians’ cooperation. His sales pitch: “Contact tracing is the way we get back as much as possible to what normal used to be like.”

But to be effective, tracing must be backed up with robust testing, Beshear said, because so many people with the virus don’t have symptoms.

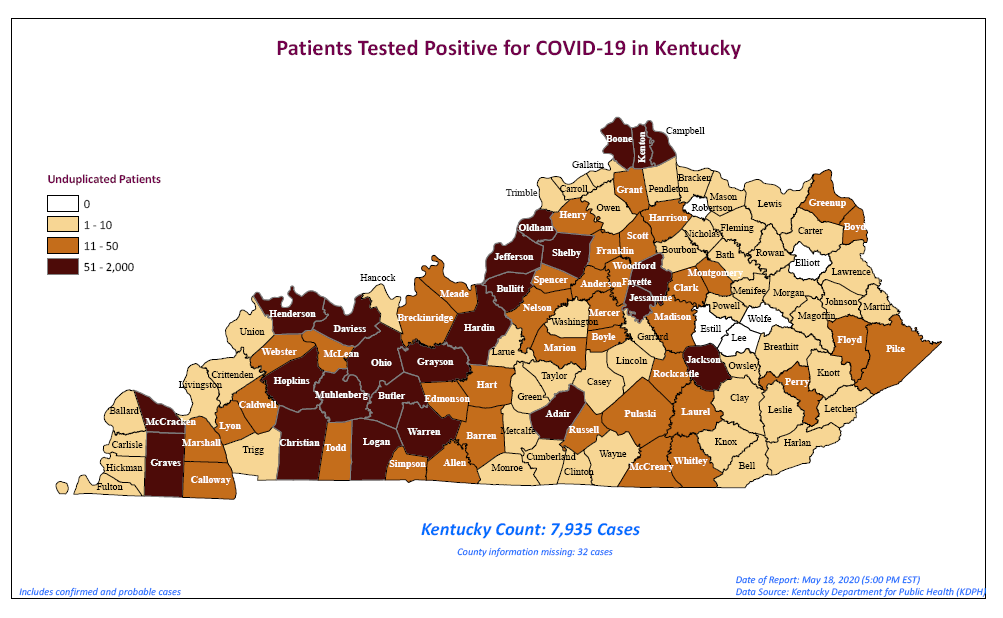

In particular, he pointed to two COVID-19 hotspots: Ohio and Graves counties, which have had very few signups for free, Kroger-sponsored testing available this week.

He said that in Ohio County, only 87 people had signed up for testing Tuesday, 45 on Wednesday and 13 on Thursday, at a site with a capacity of 300 or more spots each day.

In Graves County, he said 136 had signed up for Tuesday and just over 55 had signed up for Wednesday and Thursday combined, with similar capacity. Testing at these locations are open to anyone in the region.

“Folks, if we are going to combat this, if we are going to reopen our economy in these areas, we’ve got to do better than that,” he said.

Ohio and Graves counties are in Western Kentucky, the part of the state hit hardest by the virus. As of May 18, Graves County had 154 cases and 18 deaths, and Ohio County had 116 cases.

Melissa Patrick is a reporter for Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. She has received several competitive fellowships, including the 2016-17 Nursing and Health Care Workforce Media Fellow of the Center for Health, Media & Policy, which allowed her to focus on and write about nursing workforce issues in Kentucky; and the year-long Association of Health Care Journalists 2017-18 Regional Health Journalism Program fellowship. She is a former registered nurse and holds degrees in journalism and community leadership and development from UK.