Almost every coronavirus-related question at Gov. Andy Beshear’s news briefing Thursday ended with a call from him to get vaccinated, and that came after repeated pleas in his relatively short presentation for Kentuckians to sign up for one of the thousands of open vaccination slots across the state.

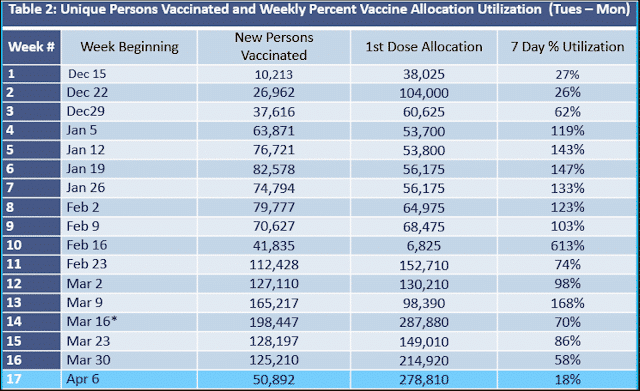

“While we vaccinated 125,210 new Kentuckians this last week, we received about 214,000 doses. So what that means is there are open appointments … not because we’re not vaccinating still at a steady pace, but because we’re getting more vaccine,” Beshear said, “so we need people to get out there and to sign up.”

Beshear again listed regional vaccine sites with thousands of slots available next week, including University of Louisville Healthat Cardinal Stadium, with more than 11,000 slots open; Kroger Health at Greenwood Mall in Bowling Green (2,000); and the Kentucky Horse Park in Lexington (1,800); Baptist Health Corbin; the Christian County Health Department (1,000); and Pikeville Medical Center (1,000).

He pleaded with Kentuckians to take whatever vaccine is available, and not wait for the single-dose Johnson and Johnson vaccine, saying Kentucky only got 7,800 doses of that vaccine this week, a drop from 65,000 last week, and state officials don’t know how many it will get in the upcoming weeks.

He said if people “wait on the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, we might not win the race against the variants” of the virus that are more contagious. He added, “It’s going to take us longer to be able to fully ease the restrictions that we all want to get rid of. So come on, get out there, get your vaccine.”

Beshear said so far, the state has detected 113 cases with “variants of concern” in Kentucky. All but two were the highly contagious B.1.1.7, which was first found in the United Kingdom. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website says 1,085 cases in Kentucky have undergone genomic testing to detect variants.

More than 1.5 million Kentuckians have received at least one dose of a vaccine, about 33% of the population.

Reluctance to get the vaccine has been reported to be more common among rural whites, especially evangelicals, and urban Blacks.

Sarah Ladd and Chris Kenning of the Louisville Courier Journal report that the real reason vaccinations have lagged among Kentucky Blacks are lack of access, including things like “little or no transportation, no internet access, few if any nearby pharmacies and struggles trying to sign up online.”

Kentucky Health News asked Beshear if these are some of the reasons rural whites have been slow to get vaccinated, or if it had to do more with politics. Beshear said that while there are some similarities between rural and urban areas, there are also other nuances that must be recognized.

He said some parts of the state have shown some higher hesitancy, naming Western Kentucky as one.

He suggested it is time to try some new strategies, like programs that offer incentives for vaccination and getting more doses into places people regularly go to, such as pharmacies and grocery stores.

The politics can be local, he said.

”Some of the areas where we see the least amount of people taking vaccines are ones where we saw local leaders push back against what we were doing to protect people” earlier in the pandemic, he said. “If you see enough of that, and someone is beating that drum beat long enough, again, it’s going to make it harder to then convince people to get vaccinated. And so we’re going to need help, both from those that have disagreed with us as we’ve gone along and those that have agreed with us to get it done.”

Beshear suggested that on Monday, he would give Kentuckians a broad incentive to get a shot: set a vaccination level at which he would remove capacity restrictions, even for events of up to 1,000 people.

“We still may be needing to wear masks, whether it’s our restaurants, our bars, our offices and the rest, [but] we can get back to that 100 percent capacity,” he said, “and it’s all dependent on how quickly and how many people we can vaccinate.”

Beshear said he thought if done safely and masking is strictly enforced, it will be safe to attend the Kentucky Derby on May 1, and he plans on being there. He also encouraged people to go ahead and get vaccinated now if they plan on being there, or anywhere that involves large crowds.

“That ought to be on anybody’s checklist who is planning on going,” he said.

Beshear said the state is tailoring some of its efforts toward young people, who he said weren’t necessarily vaccine-hesitant, but more likely indifferent because the virus has not affected their age group as harshly. He noted that young people in other states have been hospitalized with variants.

Asked about a study, published in The Lancet Psychiatry journal, that shows one in three people who have had COVID-19 have suffered a neurological or psychiatric disorder within six months of infection with the virus, Beshear said he was still looking at the study, and that he expects there will be many more like it. He also noted that Health Commissioner Dr. Steven Stack has warned all along that we don’t know the long-term effects of having COVID-19.

“Again, it has real health impacts. So get vaccinated, continue to wear your mask until we get to the end. And don’t be cavalier, because while you may think that it’s not going to hurt you, the person you could spread it to could be suffering from this,” he said.