Kentucky’s school officials got Monday what they’d long been asking for, a plan that helps them decide whether to open their schools, based on a dashboard of data that will be regularly updated – and maybe more importantly, assurance from Gov. Andy Beshear that he won’t be offering them any more advice on how to manage their districts.

“Let me be clear that there is not going to be an overall recommendation coming from me or my office, post-September 28th,” Beshear said, referring to the date he recommended that in-person schooling resume. “What’s going to be provided is the information to make a week-by-week decision in our various school districts and counties based on prevalence and what public health and experts believe is the right course based on that prevalence.”

But Health Commissioner Steven Stack said if the rate of Kentuckians testing positive for the novel coronavirus shoots up to more than 10% and hospitals are running out of beds, “We’re going to come back, and we’re going to step in, and we’re going to give different guidance.”

Stack explained that schools will need to look at two things to determine if they should be holding in-person classes: the statewide percentage of people testing positive for the virus, which needs to be under 6%, and a color-coded map that shows the prevalence of the coronavirus in their community.

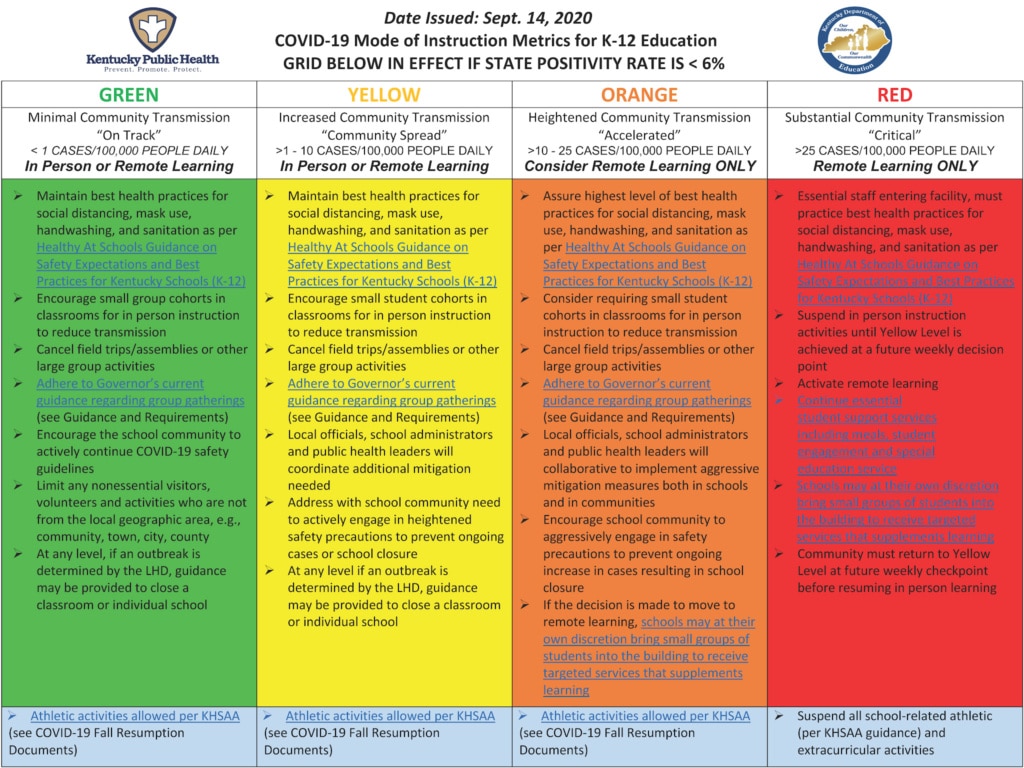

The metric-directed guidance provides a framework for schools in each category to follow. The levels are determined by the number of cases in a county per 100,000 people. (See chart, above.)

Schools in green or yellow counties are generally instructed to follow the “Healthy at School” guidance, with yellow counties encouraged to take additional precautions. Orange counties will have “accelerated” spread of the virus and be encouraged to consider remote learning only. Red counties will be “critical” and should be limited to remote learning and should cancel all school-related activities until they return to yellow status.

Beshear was asked if he would order a school in the red to move to virtual learning. “This is guidance,” he replied. “But if you’re in the red, it means there’s widespread community spread of COVID-19 and if you’re in the red, it is not responsible, it is not responsible to be doing every-day, in-person learning.”

Beshear also signed an emergency regulation to require parents and guardians of children who test positive for the virus to notify schools within 24 hours. He said the state already requires that for all communicable diseases, but he wanted to clarify that COVID-19 was included.

New data platform

The new plan involves the creation of an up-to-date dashboard that will include self-reported data from both private and public schools, including the number of new COVID-19 cases and the number of quarantined persons in their schools.

Schools will need to start submitting this data Sept. 28, but Stack said schools already doing in-person learning can go ahead and start submitting it.

Stack said his state Department for Public Health will maintain its K-12 school report, but the data will always lag behind the new dashboard and the numbers will not match up. Beshear said the dashboard is meant to provide quick information in the short term, while the public-health report will be used for long-term analysis because everything on it will have been verified.

- RELATED: Christian County’s coronavirus incidence rate is ‘critical,’ higher than discussed at school board meeting

- RELATED: Healthy at School guidance requires social distancing, mask and daily temperature checks, along with great flexibility in scheduling

Beshear said he was confident that schools would report accurate data because the public-health report would eventually reveal any discrepancies.

Stack said each individual college and university will be keeping its own up-to-date dashboard, along with the state’s public health records.

Lt. Gov. Jacqueline Coleman, who also serves as secretary of the Education and Workforce Development Cabinet, said she will be working with the health department and the Department of Education to hold town halls with superintendents, teachers and other stakeholders about the changes: “Our goals are to be transparent and communicative, to ensure accountability and inclusion and to allow every voice to be heard.”

Dr. Houston Barber, superintendent of the Frankfort Independent Schools and a student of analytics in the Harvard University Business Analytics Program, praised the new program.

“As a father of four … I empathize with all Kentuckians about what school looks like today and how you’re navigating that course,” Barber said. “This tool that has been developed for K-12 is incredible. It allows for districts all across the state of Kentucky to work together with their local health officials, to work with their local board teams and come up with a strategy that makes sense for their students, for their families and for their communities.”

In Lexington, which has seen a surge of cases partly driven by students at the University of Kentucky, Fayette County school officials said they wouldn’t resume in-person classes “until at least after the fall break on Oct. 1 and 2 … as a group of parents rallied outside Central Office for an immediate return,” Valarie Honeycutt Spears reports for the Lexington Herald-Leader.

Melissa Patrick is a reporter for Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. She has received several competitive fellowships, including the 2016-17 Nursing and Health Care Workforce Media Fellow of the Center for Health, Media & Policy, which allowed her to focus on and write about nursing workforce issues in Kentucky; and the year-long Association of Health Care Journalists 2017-18 Regional Health Journalism Program fellowship. She is a former registered nurse and holds degrees in journalism and community leadership and development from UK.