The golden hue of the sunset shines across the sky and through the window as a woman drives down Van Meter Road in central Kentucky’s Clark County, passing by green rolling hills and hay bales.

In her social media video from early September, Adreanna Wills points out white signs in yards along the way, displaying the phrase “Industrial Solar” with a slash through the words.

“Imagine these signs being ‘for sale’ signs in front of these properties instead of the signs demonstrating where they stand on this, because that’s probably what we’re looking at for some of these families,” said Wills, who runs the county animal shelter.

For months beforehand, the Winchester-Clark County Planning Commission had been considering an ordinance that would amend local zoning to allow for solar projects to be installed in agricultural zones, or on flat, sunny farmland. Clark County already had one solar installation, in the form of 32,300 solar panels on 60 acres, producing up to 8.5 megawatts of electricity, run by the East Kentucky Power Cooperative since 2017.

But the solar farms the local government is now considering under the ordinance would be much larger, spurred on by Massachusetts-based Swift Current Energy looking to build a solar project with a capacity of 220 megawatts. Some in Clark County, especially farmers, have concerns.

“I don’t necessarily think industrial solar is wrong. I don’t even think it’s wrong for our community. But I think the way that they have gone about it is wrong,” Wills said in a recent interview. “The process has not been followed the way that it should.”

Hundreds of people attended a special commission meeting about the ordinance in September, lining up out the door of a local church, with some wearing masks with logos opposing the solar project. The meeting was ultimately canceled due to legal issues. Even with commission meetings held virtually due to the pandemic, Wills said she feels like the community hasn’t yet had the needed forum to fully weigh in on the ordinance.

“I don’t even know that the industrial solar is the huge issue behind this and why the community is pushing back so much,” she said. “I think the issue is more about the leadership and the way the process has been handled.”

She said one of the reasons she drove down that particular road in September was to show people the community’s agriculture. Depending on the time of year, crops could be growing and cattle could be grazing in those fields. Her family roots are in farming, and she wants to make sure farmers’ voices are heard when it comes to how the land is used.

For a community in the Bluegrass region that values farmland as a key part of its identity, the solar industry knocking on its door presents an opportunity and a potential turning point for its future land use. It’s a scenario that could become more common around the region as President Joe Biden pursues an aggressive clean energy agenda.

Biden signed a series of executive orders last month directing federal agencies to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies and invest in carbon-free electricity, among other actions. The administration’s push and positive market forces for renewable energy will make the public processes for placing solar power more important, even in a region long dominated by fossil fuels.

‘Ag’ Issues

Wills said she didn’t become aware of the solar ordinance until a local organization brought the issue to the community’s attention. The Clark Coalition formed last June, advocating for smart economic growth and government transparency. It’s gotten support particularly from farmers, including its executive director Will Mayer.

“Clark County is a very significant agricultural sector. It employs nearly 1,400 people. It has a $200 million annual economic impact. And it also is very central to our ability to attract investment, and tourism, and residents,” Mayer said. “It’s really about quality of life.”

Mayer said he first learned about the ordinance and the related solar project being considered that summer, but the conversations surrounding the project had been reportedly happening between local government and Swift Current Energy for more than six months before then, unknown to the broader public.

“It’s now been 18 months since these initial conversations between the developers and some of our local officials first took place, and the public has still yet to have had the opportunity to weigh in on this issue,” Mayer said. “The community should decide whether or not it wants this land use. And then if it does, then we look at how do we regulate it.”

He said the Clark Coalition isn’t opposed to solar energy as a whole, but believes the community should have the proper forum to talk about industrial solar on productive farmland, which the organization is against. While the commission most recently held virtual working sessions in December regarding the ordinance, Mayer said poor internet connection at times hampered the public’s ability to listen in.

Local cattle farmer John Sparks, who supports the coalition, worries how much highly productive farmland could be taken out of commission by an industrial solar project.

“This area right here in central Kentucky is a magical place for livestock,” Sparks said. “If you want to do solar panels, find the places not special as this, and do it. But this is too special of a place. This shouldn’t be happening on this type of land.”

Sparks isn’t necessarily against solar energy either, but believes it could be better placed on tops of warehouses or residences.

The Clark Coalition in a December letter to local government called for a one-year moratorium on solar development and the consideration of the ordinance to allow for a more substantive conversation about the issues at hand, while referencing the county’s comprehensive plan which details how land should be used in the coming decade.

“I could have told you that it would not go smoothly, because there were a lot of very justifiably upset people who felt that they’ve been excluded from the process,” said Tom Fitzgerald, director of the Kentucky Resources Council.

Fitzgerald, a prominent environmental advocate, was brought in by the Clark Coalition early in the group’s efforts, but isn’t involved with the group currently. His nonprofit aiming to protect communities from pollution and environmental damage created an ordinance template last year to help Clark County and other communities navigate land use issues with solar projects.

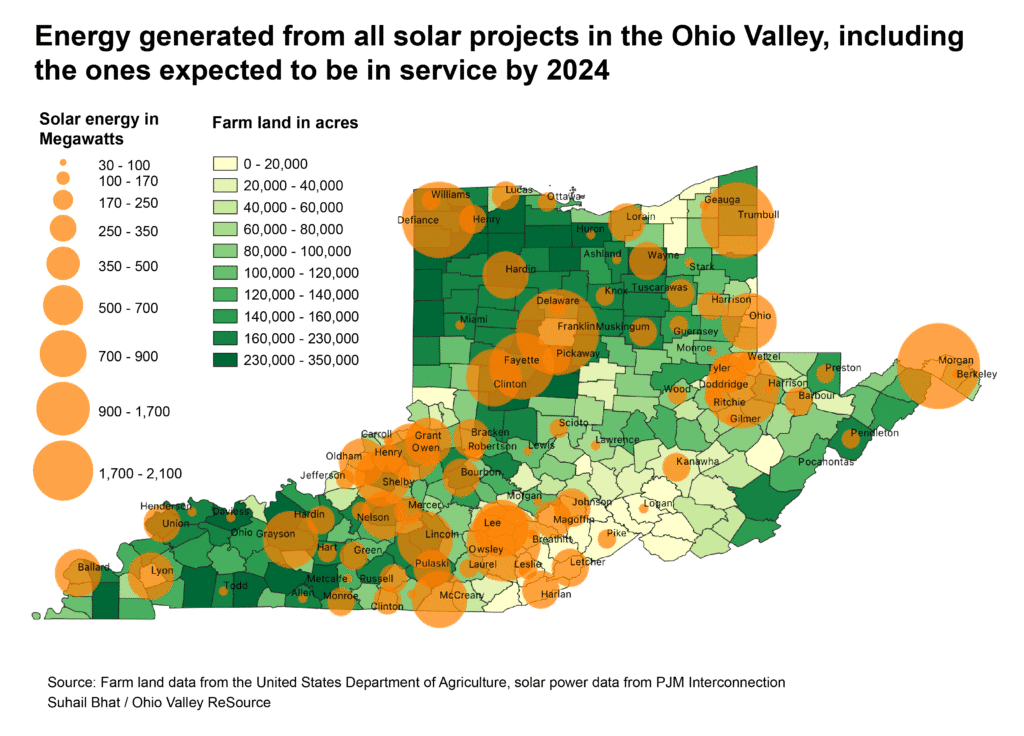

As for where solar farms should be placed, Fitzgerald said much of it is dependent on access to regional transmission grids. In Clark County’s case, Swift Current Energy would offer its electricity to the PJM grid, acting as a wholesale electricity provider. In Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, upwards of 250 active solar projects are already connected or plan to be connected to the grid, according to PJM. Swift Current Energy declined an interview for this story.

Fitzgerald said for a project like the one in Clark County to succeed, the conversation between the developers and community needs to be ongoing and candid. But Fitzgerald and other solar advocates also see opportunity in Appalachia.

Growing Solar

For a region that’s traditionally been dominated by fossil fuels, Joey James with the West Virginia-based consulting firm Downstream Strategies believes the

Ohio Valley is on the front edge of opportunity for solar.

“What we know is that 85% of solar development that’s happened historically in the United States has been concentrated in 10 states,” James said. “Generally they’re found on the coasts.”

According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, less than 1% of all electricity in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia is produced by solar energy. James said this positions the region to take greater advantage of “carbon offsets,” or credits that companies can use to meet sustainability goals. Because the region still relies heavily on fossil fuels, the carbon offset incentives can be just as important to solar companies as making profit from electricity.

And with hundreds of thousands of acres of degraded lands from a history of mining and burning coal available for solar installations, he said, the opportunities could be transformative.

“You can achieve quicker and deeper carbon offsets here than if you were to just build another solar farm in California,” James said, referring to a recent study from his firm. “What better place to do that than on former coal mines and industrial sites that played such a large role in the growth and expansion of our nation.”

Research from the energy consulting firm Wood MacKenzie also found utility-scale solar could be the cheapest form of power generation in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia by this year or next.

But James also cautioned that the transition from fossil fuel reliance could be a slow process. A recent report from the West Virginia University College of Law urged the state to embrace renewables for a better economic future, while also dispelling the notion that coal is still a cost effective form of power generation.

Smart policy and open communication with stakeholders can make solar power a good fit for farmers. One eastern Kentucky farmer is already seeing savings from solar energy on a smaller scale.

Bryce Baumann helps manage a 300-member community-supported agriculture farm in Garrard County and Madison County, where the construction of an 1,100 acre solar farm is moving forward. He decided to install solar panels last year as a way to manage costs from an energy-intensive operation, while also taking into consideration their environmental responsibilities. His monthly electricity bill from his local electric cooperative has plummeted as a result, from $300 to $18.

“Farms are inherently solar energy generators, whether we might turn it into electricity or cellulose,” Baumann said. “It just makes sense to look for all the ways that we can to generate our own electricity and decrease our impact.”

Baumann said he worked with the Mountain Association, an economic development organization focusing on eastern Kentucky, to receive grants at the federal and state level to support the solar installation.

A Plea For Process

Clark County Judge-Executive Chris Pace is one of those concerned about the displacement of coal by incoming renewables.

“It just seems like the federal government has a grudge against coal, especially a Democratic administration. And so that’s what is kind of pushing people into a corner in regards to what to do with solar,” Pace said.

While he said he’s open to the idea of solar energy, he worries about “federal mandates” on solar energy at the local level, and also wonders what solar installations could mean for the use of farmland.

When asked about complaints regarding a lack of transparency and public input in the consideration of the local solar ordinance, he said he’s confident that it’ll have a public hearing, whether before the planning commission or the city and county government.

“I don’t really know that you can require a private business to hold open hearings on their own. But once [the ordinance] becomes something that’s discussed in planning and zoning, of course, it’s going to have a public airing,” Pace said.

For Adreanna Wills, communication is key to moving forward in this process.

“These are the people that are going to be living beside of it,” she said. “So we’ve got to come up with a better process or a better plan of getting people on board if it’s going to be successful.”

(Editor’s note: This story was modified on Feb. 20 to clarify the Clark Coalition position on siting solar facilities.)

Liam Niemeyer is a reporter for the Ohio Valley Resource covering agriculture and infrastructure in Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia and also serves Assistant News Director at WKMS. He has reported for public radio stations across the country from Appalachia to Alaska, most recently as a reporter for WOUB Public Media in Athens, Ohio. He is a recent alumnus of Ohio University and enjoys playing tenor saxophone in various jazz groups.