Under the gun of new pension rules, Kentucky’s health commissioner wants local health departments to drastically cut services, but he says the departments need the legislature to give them one more reprieve from big pension bills that would put dozens of them out of business in the next 12 months.

Dr. Jeffrey Howard, the health commissioner, says his plan calls for a system that would assure the survival of public health in the state, and would ultimately improve the state’s health outcomes.

Howard created this new model largely in response to the state’s pension crisis, which on July 1 will require health departments to increase their pension obligation from 49.47 percent to 83.43 percent of payroll — unless a special session of the General Assembly changes that.

In the regular session that ended in April, Gov. Matt Bevin vetoed a bill that would have offered some temporary relief to health departments. He has said he will call a special session to deal with the issue, but he and legislators have yet to secure the agreement and votes needed to pass a bill into law.

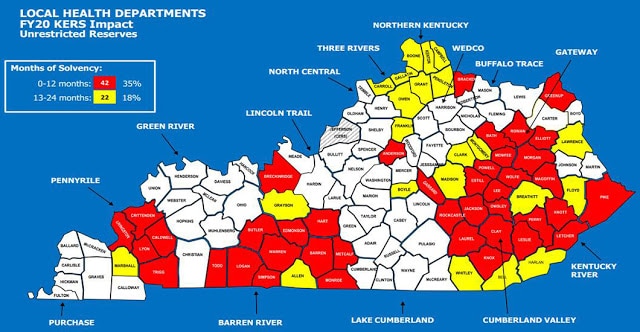

Without any relief from this added pension contribution and everything remaining the same, Howard’s Department of Public Health says 42 health departments would close in the next 12 months, and 22 more would run out of reserves and be forced to close in the the next 24 months.

A taxing situation?

One of the departments most in danger, in Anderson County, recently raised its local property tax from 30 cents per $1,000 in assessed valuation to 52.5, cents to pay for its possible extra pension obligation, Ben Carlson reports The Anderson News. Without relief from the added pension liability, the agency is slated to pay an extra $140,470 a year.

However, raising local taxes doesn’t seem to be a popular option among the 113 counties that have a health tax.

Of the 23 counties that have reported their tax rates for the coming year, only five have proposed an increase, and minutes of the local health board meetings do not indicate that the increases are being driven by the need to cover higher pension costs, said Mike Tuggle, the state health department’s assistant director for administration and financial management. He said in an email that the department will continue to receive tax resolutions through early October.

Using local tax dollars to fund public health would result in huge inequities, said Scott Lockard, director of the Kentucky River District Health Department, which covers some of the state’s poorest and unhealthiest counties.

“Communities that need public-health services the most, that have the highest poverty rate, that have the poorest health outcomes, also have the least ability to raise local revenue,” Lockard said. He added that when he was the health director in relatively wealthy Clark County, his tax base was about the same as it is for all seven counties in his district, which has about three times as many people.

“In Eastern Kentucky, we cannot raise enough local tax revenue to address this problem. And shifting the burden from the state to the locality is just not going to work for these poor communities,” he said. He added that Howard’s new plan is designed to address some of these inequities.

Crisis = Opportunity?

Howard says the crisis has created an opportunity.

He told a statewide board of health meeting in January that the state can take the opportunity to move away from a public-health system that is “an inch deep and a mile wide” and transform it in a way that will improve health outcomes across the state. “This is truly an opportunity to transform a system that has needed transforming for many decades,” he said at the meeting.

Howard’s plan calls for departments to scale back their services, and only be required to provide four “core public health” areas. He said it doesn’t matter if the department implements these programs or if a community partner does, only that the department is committed to making sure they are in place.

The core areas include: foundational public health services, five areas that are required by law or regulation; the Women’s, Infants and Children nutrition program; the HANDS program, which stands for Health Access Nurturing Development Services for child rearing; and harm reduction and substance-use disorder programs, including syringe exchanges.

The plan also requires health departments to perform community health assessments, which many of them already do, to determine their local public health priorities beyond those core requirements.

However, under Howard’s new plan, before a department could implement a program to address a local need, such as diabetes management, it must first see if the need is already being addressed elsewhere, and if it is, they would be asked to work with that agency to either support or complement its program instead of creating a new one.

If the need is not being met in their community, a department would then have to present its proposed program to a newly formed advisory board, which would review the request to make sure it meets a list of five criteria, including whether it is data-driven, offers an evidence-based solution, is adequately funded, includes a performance and quality management plan; and has an exit strategy.

At the January meeting, Howard said the plan has the support of the Kentucky Health Departments Association, the Kentucky Association of Local Boards of Health, the Kentucky Public Health Association and the University of Kentucky‘s Center of Excellence in Rural Health. The health-department association has long promoted a similar model called “Public Health 3.0,” on which Howard’s plan is based.

Howard said the plan also has the support of his colleagues at the health department and Gov. Matt Bevin. He said it will be introduced to lawmakers during the 2020 session, noting that it will require “some overwhelming legislative buy-in.” He also said he needs lawmakers to hold the pension rate at 49.47% for one more year to give him time to get this plan in place.

The new model has already been embraced at the Kentucky River department, which covers Knott, Lee, Leslie, Letcher, Owsley, Perry and Wolfe counties.

Why? “We are one of the most financially fragile health departments in the state,” Lockard said. “We are redirecting our resources just to our foundational services, and basically we’re going to be focusing on what we are statutorily mandated to do.”

Under the higher pension rates, the Kentucky River department’s extra pension obligation is about $1.3 million each year, and it has less than one year of unrestricted resources available before it would be forced to close, according to a spreadsheet provided by Tuggle. That makes it the fourth-worst-off department in the state.

Lockard said he has been working for the last year toward this “public health transformation” model. He said his agency has cut its payroll costs by $900,000, renegotiated contracts with pediatric therapists, is working toward referring all cancer screenings out of the department, and will be discontinuing all maternity services.

Bottom line, he said, if a program is not financially viable or is not statutorily mandated, it must go. And if somebody else can meet the need in the private sector, we need to let them do it.

He ended his interview with a warning: “I feel like we are facing truly a tipping point in public health, that if we do not make the right choices now and put a sustainable public-health funding model in place, the health outcomes for the people of this state are going to be impacted for generations.”

(Kentucky Health News is an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky.)

Melissa Patrick is a reporter for Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. She has received several competitive fellowships, including the 2016-17 Nursing and Health Care Workforce Media Fellow of the Center for Health, Media & Policy, which allowed her to focus on and write about nursing workforce issues in Kentucky; and the year-long Association of Health Care Journalists 2017-18 Regional Health Journalism Program fellowship. She is a former registered nurse and holds degrees in journalism and community leadership and development from UK.