For more than three years, I’ve written about COVID-19. The people who caught it and those who kept it longer than they should have. The people who bought into misinformation. And, worst of all, those who died from it.

Finally, I tested positive myself.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve had several COVID-19 scares over the last few years. In early 2020, before tests were available to young and healthy people, my doctor at the time believed me to have it. But she couldn’t spare a test for me, so we never knew for sure. Since then, I’ve had several flu-like bouts, but always got “negative” back from COVID-19 tests.

That changed on Wednesday, Oct. 4, 2023. And now that I have hard confirmation of a COVID-19 infection, I see that nothing I experienced before compared to this. Does that mean this is my first true bout with the disease? Maybe I’ll never know.

Here’s what I do know. I’ve come to understand COVID-19 during my time in isolation in a way I never did before.

There’s a sick sort of forced independence in this illness. No one can rub your back when you ache or hold a cool rag to your fevered head. Getting a comforting hug? Out of the question.

While lying on my back in air that felt heavier than it ever had before, I thought to myself: No wonder COVID-19 is so divisive. We deal with it alone. Without seeing a smile or feeling a pat on the back. Without humanity.

Similar isolation is true for other illnesses, but this was all new to me.

All these things I knew — in theory. I’ve sat through enough press conferences with infectious disease specialists to know COVID-19’s symptoms backwards and forwards. But I think I fell into the age-old trap of never expecting a thing that affects other people to affect me as bad or the same. And my idea of a COVID-19 infection was, I realize now, very clinical. Distanced.

I’d been renovating my house the day I tested positive. All day long, I scraped old paint from 100-year-old wooden door frames. Too busy to check in with myself, I never stopped to question why I kept having to sit down because I felt like I might pass out.

By the end of the work day, my throat burned and the air was heavy around me. I gasped for air, but thought maybe I was just tired from a day of physical labor. Better take a test just to be safe, I thought. My nose burned and throbbed when I stuck the cotton swab up one nostril, then the next.

My 15-minute timer wasn’t two minutes in when a deep red dash popped on the second line of the at-home test. A “positive” indicator. Oh well, the instructions say not to read the test before 15 minutes. So, I left the bathroom and came back at the 15-minute mark. Two bright red lines. Positive.

I had a few thoughts in quick succession: I just unknowingly exposed my friend to the virus the night before and needed to let her know. I’d have to miss another friend’s birthday party over the weekend. And, finally, well, I’m young and healthy. This will run right through me.

It was a mistake to think that. Over the next few days I’d lose my sense of smell and taste. I’d grow weaker until I could barely walk across a room without a break. All of my strength disappeared. I’d go on Paxlovid within days.

Through all this, I abandoned the subconscious idea that people under 30 don’t suffer. But – I still consider myself extremely fortunate to not have ended up in a hospital, like so many have before me.

After testing positive, I withdrew to the attic to isolate away from my dog and spouse for the recommended five days.

In isolation I felt humanity slipping from me. My friends can tell you I am a notorious introvert. But this level of aloneness was new, unwanted. I heard my dog, Ronon, cry for me at the bottom of the stairs. He could not understand why we had to be apart, that he could catch it. I was afraid to touch anything in my bedroom, worried I’d contaminate everything and hyper aware that anything I touched now would need to be sanitized later.

I feel like a walking plague, I texted my friends.

So, I cataloged my very existence. I touched the door handle to the bathroom, my jewelry box. What have I forgotten? What have I breathed on?

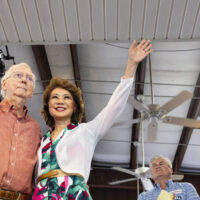

With no smell or taste, I laid strong mint toothpaste across my tongue to try and feel. Nothing. COVID-19 is the first illness that ever robbed me of my senses. It was disorienting and depressing. I grasped at sensations but found little to satisfy. The Paxlovid made my eyes burn. So for days, I did little but sleep. Eyes closed. No strength, no scents, no taste — except for the disgusting “Paxlovid mouth.” All this felt like a horrible limbo, like my life had stopped at the door to the upstairs. Sarah reuniting with her dog after leaving COVID-19 isolation.

I decided to post on social media about having the virus. I thought little of it, until comments riddled with misinformation about COVID-19 poured into my mentions.

The rhetoric from 2020 and 2021 about vaccines not working, COVID-19 being nothing more than a cold, and more flowed in after I posted about my experience. It was frustrating to hear the debunked myths thrown at me in a moment of vulnerability.

Much of my role as a COVID-19 reporter has been — and still is — unpacking misinformation. But my mentions after posting about my COVID infection told me we have a long way to go in educating people about the virus.

Indeed, three years in, I wonder if we may never fully get there. But I promise to keep trying.

How can we face a pandemic in unity and with compassion when they’re stripped from us when the virus comes for us? I don’t know the full answer to that, but I think it involves putting in a lot of work toward empathy. As we continue to deal with COVID-19 and its fallout, I hope we can try to come together on that one singular point, if nothing more.

As for me, I’ll never again take for granted the smell of a pumpkin candle in the fall, the greasy french fries at my favorite restaurant, or the way it feels so good to move my legs.

My strength is returning a bit more each day, and I’m able to go for walks again and wrestle my dog. I feel my other senses returning, too, despite being a bit slower than I’d like.

Every day, I feel such gratitude to be alive, to breathe.

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.