The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 83 years ago Dec. 7, spun off “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” one of the most famous American war songs. But the tune’s Kentucky connection is largely unknown.

The “ripsnorting battle hymn of the Navy” was inspired by Chaplain Howell Forgy, 34, who left the pulpit at Murray First Presbyterian Church to join the Navy in 1940.

The Sunday morning air raid that plunged the U.S. into World War II naturally canceled church services all over the sprawling Navy base on Oahu and aboard the dozens of warships at anchor. Forgy encouraged his flock on the USS New Orleans to “praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.”

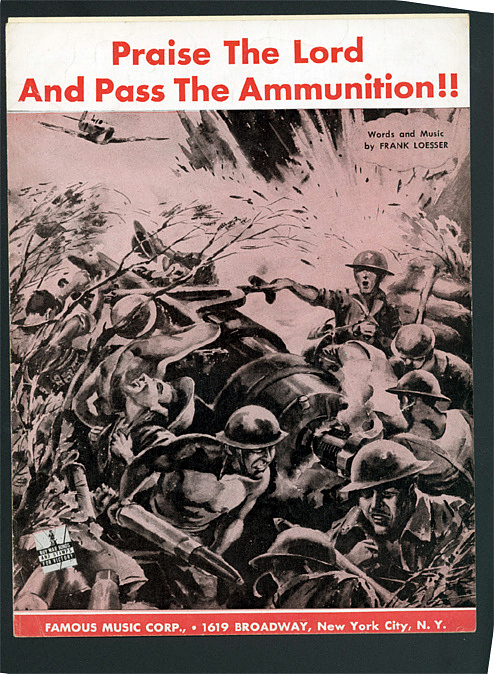

Written by Frank Loesser, it “was the first war song to register as a best-seller on the popularity charts,” according to “God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War” (University Press of Kentucky, 2003) by Kathleen E.R. Smith, who added that “in just a few weeks, it sold more than 170,000 copies (with Loesser donating all royalties to Navy Relief.)”

Popularized by Kay Kyser and his orchestra and also sung by Bing Crosby, the song “spent three months on Variety’s ’10 Best sellers List,’ sold over 450,000 copies of sheet music in two months and was, for a while the best hope for Tin Pan Alley [an area in New York noted for songwriters and music publishers] to repeat the success of “Over There,” the immortal World War I tune, Smith wrote.

Forgy’s photo in uniform still hangs on the wall of the red brick church from which he departed with a bride, choir member Louise Morgan, then a 23-year-old Murray State College student from Princeton.

The Forgys retired in California where he died in 1972; Louise lived until 1996.

His book, “… And Pass the Ammunition,” includes one of the most detailed accounts of the raid that led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare Dec. 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy.”

Forgy started the morning daydreaming about Murray and the church. He was still in his bunk just before 8 a.m. — nearly noon in Murray — when swarms of enemy warplanes, flying off six aircraft carriers, unleashed a lethal rain of bombs, torpedoes and strafing fire on Pearl Harbor. (The attackers also pounded Army, Navy and Marine air bases on the island of Oahu.)

Forgy figured that church was just letting out in Murray. The book described the faithful: “high-school teachers, college professors, farmers in their Sunday bests and squeaky shoes, the village merchants and their wives milling about on the lawn of the little red brick church.”

While many other ships and crewmen were lost in the attack, the New Orleans suffered no casualties and only slight damage from bomb fragments.

At first, Lt. (junior grade) Forgy didn’t get credit for saying “praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.” The distinction went to Capt. William A. Maguire, a Catholic priest and chaplain of the whole Pacific Fleet. The song didn’t name Forgy or Maguire, but the lyrics had a Navy “sky pilot” putting down his Bible, manning a gun and shouting, “Praise the Lord, and pass the ammunition!”

Maguire and Forgy vehemently denied shooting at the Japanese because the Geneva Convention prohibited chaplains from fighting.

Maguire ultimately admitted he couldn’t recall saying the famous words, though he said they expressed his sentiment.

Forgy wasn’t looking for publicity or praise. But he explained to an Associated Press reporter. “The boys were getting dog-tired. All I did was slap them on the backs and smilingly say, ‘Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition, boys.’”

According to Smith, the song was a hit, but not with everybody. Some Seattle pastors panned it as “a jazz tune of blasphemy against Christ and the church,” the British United Press reported. “Clerics of several faiths made public statements which held the song as sacrilegious.”

But the song earned plaudits from some other congregants and clergy. Until the Japanese surrendered in 1945, members of Denver’s Liberal Church recited the Lord’s Prayer and sang “Praise the Lord” at the end of every service. At a Brooklyn temple, a cantor who usually sang “O Jerusalem” as a standby made “Praise the Lord” part of the service.

Meanwhile, John O’Donnell, New York Daily News Washington correspondent, knew a juicy story when he saw one and jumped on the “Praise the Lord” controversy. He claimed, tongue-in-cheek, that the dispute over who said, “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition” promised “to become as historic as the [Sir Francis] Bacon-[William] Shakespeare feud” over who really wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Besides, he added, the Office of War Information’s blessing on the “ripsnorting battle hymn of the Navy” put the agency in a bind over “sanctioning an act by a chaplain in direct violation of Navy regulations, as well as the Geneva Convention,” O’Donnell wrote.

An Office of War Information spokesperson advised O’Donnell, “We’re not interested in the authorship of the chaplain’s phrase. … It’s the song itself that the Office of War Information endorsed. The song has guts. It isn’t namby-pamby and doesn’t stink like most of the stuff that has been written since we entered the war.”

Ultimately the controversy faded, and “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” is ranked among the greatest American patriotic war songs.

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Berry Craig, a Carlisle countian, is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of seven books, all on Kentucky history. His latest is "Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy" which the University Press of Kentucky published.