“Many a farm woman has had her life shortened by carrying water from the well or spring, bending for hours at a time over steaming washtubs and doing other hard labor from which the women in town long ago were emancipated.” — C.V. Gregory, “Back to the Farm, IV. The Modern Farm Home,” The Hopkinsville Kentuckian, Sept. 22, 1910

White families may have owned the homes lining Hopkinsville’s East Seventh Street in the early 20th century, but Black women frequently kept them running. These women were members of a few families who disproportionately represented the domestic workers on this street.

Buckner, Henry, Maddox — it took dedicated digging to find these names. They are the maiden names of at least six women who worked on these two blocks of East Seventh Street. Just reading a census record, no one would know they were related. Their married names don’t match. It’s only after peeling back the pages of the records that the undergirding family ties begin to appear.

The Laundry

Where did the Daltons do their laundry? This was a burning question that kept me awake at night! My best hypothesis was that the large basement room beneath the dining room had originally been for laundry. Since the house was built with plumbing and a full basement, it’s not a stretch of the imagination to expect to find a laundry there.

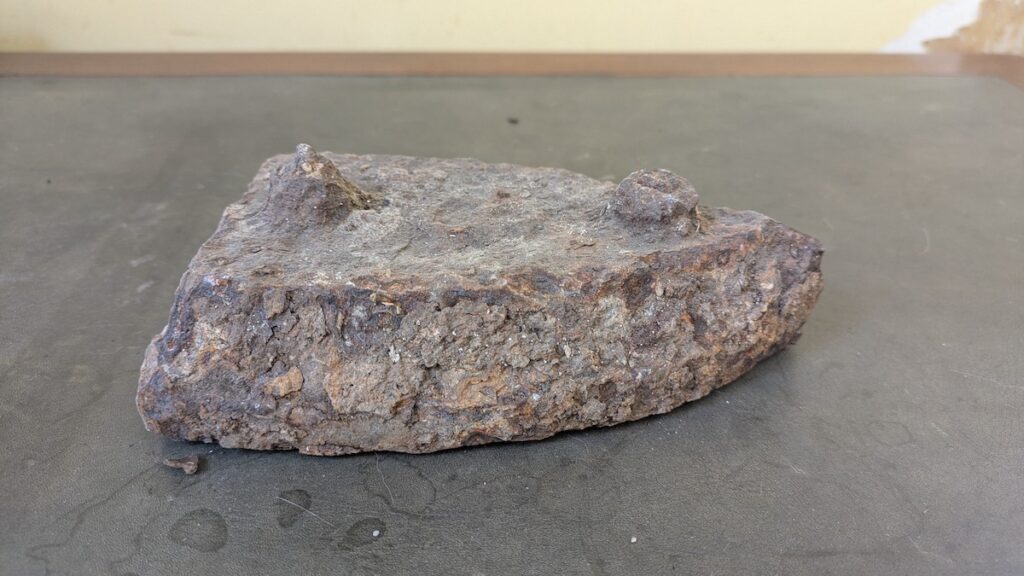

A circa 1907 laundry space would have been comprised of a tub or deep sink, maybe some racks for hanging wet sheets and clothes, and a large table for ironing. Despite the appearance of technological progress created by indoor plumbing, the real washing work would have still been done by hand, on an invention from a century earlier — the washboard. A drain in the floor, along the long back wall of our basement, strengthened my belief that this room could have originally served as the laundry. In fact, one of my prize finds is an old iron, which I unearthed while digging in the strip of garden that lines the west side of the kitchen ell, which is a wing of the house that is perpendicular to the main house.

Several months ago, I was able to get my hands on a copy of Sarah Dalton Todd’s memoir, “Quality Hill,” and she enlightened me on this point. Amazingly, Sarah mentioned that Kate Maxie, who lived in the Blooming Grove community north of town, ran a laundry service, and that the Daltons were one of her clients. According to Sarah, Kate and her husband John would arrive at the Daltons’ in a creaking horse-drawn wagon, typically after dark on a Saturday night, to drop off clean laundry and pick up the next load to be washed.

Without Sarah Dalton Todd putting Kate Maxie’s name into print, this little bit of history would have been lost. Kate Maxie’s story is a remarkable window not just into the life of a Black female business-owner in turn-of-the-century Hopkinsville, but also into the connections among the Black women who worked on East Seventh Street.

The Buckners

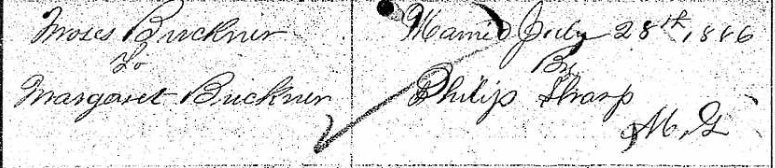

Kate was born to Moses and Margaret Buckner in 1876, their fifth child of at least 10. Both of her parents almost certainly started their lives as enslaved workers, potentially on the same farm. Their 1866 marriage record, shortly after emancipation, lists them both with the last name Buckner. It’s apparent, from the wide range of birth dates and ages claimed on census records, that neither knew their actual birth date.

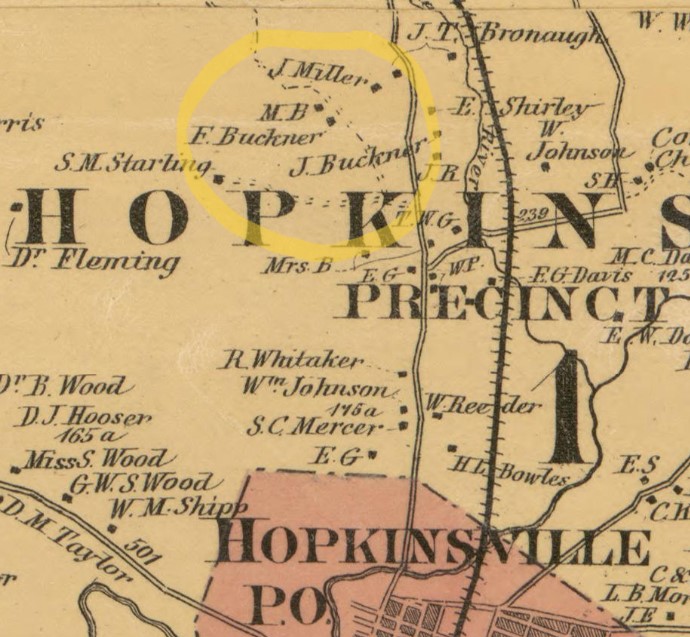

Moses and Margaret Buckner owned a small farm in Blooming Grove, a community about two miles north of Hopkinsville, on the west side of Madisonville Road. Land ownership was an achievement many Black folks across the South strove for but never attained in the Jim Crow years. So the fact that Moses Buckner owned his farm is significant.

In 1880, this farm was 22 acres. Just two acres were improved; the other 20 were woodland. Although Moses Buckner’s occupation on census records was always recorded as farmer, it seems likely he may have done more logging and timber sales than planting and harvesting. In 1880, he had one milk cow and nine pigs but no crops.

Moses and Margaret Buckner had at least 10 children together. The oldest child in the household, Cornelia, was born in 1863, and was not Moses’ child. When Cornelia died, her brother Ira gave the information on her death certificate, and he named her father as Tom Buckner. This suggests that Moses and Margaret were not a couple until after emancipation, when they first had the autonomy to choose a spouse.

The Life of a Laundress

As a laundress, Kate Maxie was a domestic worker, and her labor was foundational for keeping the households she serviced running. Unlike cooks and maids, she would have set her own schedule and could have worked out of her own home or in her client’s laundry facility. Laundresses had a stereotype of being unladylike, as they were usually strong, independent, and mostly uneducated. Being a laundress was a demanding job, but it offered more autonomy than the life of a cook or maid, the other occupations accessible to Black women in the Jim Crow South.

Doing laundry by hand was back-breaking and time-consuming work. It usually required moving heavy buckets of water by hand, scrubbing and literally beating the dirt out of soiled sheets and garments, hanging the clean laundry to dry, ironing (which also meant keeping a fire going and managing at least two hot irons), and folding. White sheets and clothes were additionally treated with blue dye, usually made of indigo or Prussian blue pigment, to counteract yellowing. This practice is still observed today; it’s why liquid detergent is blue and dry detergent includes blue beads.

A laundress was left exhausted, stiff, and with sore, cracked skin, and burns. I think it’s clear why, in 1907, laundry was a task that anyone who could afford to pay someone else to do, did. In fact, laundresses were the most numerous domestic worker in 1910s Hopkinsville and America. The 1914 City Directory for Hopkinsville enumerates over 500 women—almost all Black—who worked as laundresses! One of these was Oza Bracken, Kate Maxie’s youngest sister. For comparison, laundresses outnumbered cooks in the 1914 Hopkinsville City Directory by over 100.

Sibling Solidarity

The Buckner siblings stuck together. One daughter, Charity, married and moved to Evansville, and eventually her brother Moses moved in with her. They shared a home for the rest of their lives. Two other siblings, Ira and Cornelia, also lived together for a number of years.

So it’s not surprising to find that Kate Maxie wasn’t the only Buckner who worked for the East Seventh Street Daltons. Her older half-sister, Cornelia Wooldridge, cooked for George and Ada Dalton, who lived on the corner of East Seventh and South Campbell streets, for at least 15 years.

Did Kate Maxie also do George and Ada Dalton’s laundry? We’ll likely never know. But I think it’s clear that the Buckners utilized their network of professional relationships to help their own extended families. There are certainly numerous intersections between the Buckners and Daltons. Aside from Kate and Cornelia, John Maxie and Ira Buckner both worked at the Dalton Bros. brickyard at various times.

Cornelia Wooldridge

Before she came to cook for the George Dalton family, Cornelia’s life seemed to be heading in a much different direction. In 1881, she married Lee Wooldridge, a carpenter. By 1900 the Wooldridge family had left Hopkinsville. They lived in Madisonville with their two children, Lee’s sister, and a boarder. Lee must have done well financially, and Cornelia doesn’t appear to have worked. In 1902, she gave birth to their third child, Charlie.

But by 1910, Cornelia’s situation had changed dramatically. It seems that Lee died sometime after Charlie’s birth, and Cornelia moved the family back to Hopkinsville. This was likely a move back into the safety net of her family, who could help support her as a single mother.

Without Lee’s earnings, it was necessary for Cornelia to work to provide for her family. By 1910, she had found her position as George and Ada Dalton’s cook, where she stayed for the next 15 years. Cornelia was not a live-in cook. Rather, she worked on East Seventh Street during the day and returned to her home on Vine Street at night.

Who knows — maybe she sometimes hitched a ride home on Kate and John Maxie’s wagon.

Kate’s Fate

Sarah Dalton Todd noted in her memoir that both Kate and Cornelia “lived to a ripe old age.” This wasn’t quite true.

For a woman who must have led an active life, Kate Maxie’s end came swiftly. She died in December 1918, just 43 years old. While her death certificate lists pneumonia as the cause, this condition was almost certainly brought on by the Spanish flu, which she was hospitalized with in November. The Spanish flu was notorious for attacking healthy people in the prime of life and was no respecter of class or rank — Lucien Davis, Monroe Dalton’s brother-in-law, also died from it that November.

Cornelia Wooldridge worked for Ada Dalton, staying on after George Dalton’s death in 1922, for the rest of her life. She died in 1925 of neuritis and acute rheumatism. She was 62 years old.

All history, just like the present, really is a snapshot in time. Sarah Dalton Todd’s reminiscences of the Black women who worked are a gift of indescribable magnitude. Each name is a key that reveals lives lived and, until now, perhaps forgotten.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.