The United States is the only democracy in the world where a presidential candidate can get the most popular votes and still lose the election. Thanks to the Electoral College, that has happened five times in the country’s history. The most recent examples are from 2000, when Al Gore won the popular vote but George W. Bush won the Electoral College after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, and 2016, when Hillary Clinton got more votes nationwide than Donald Trump but lost in the Electoral College.

The Founding Fathers did not invent the idea of an electoral college. Rather, they borrowed the concept from Europe, where it had been used to pick emperors for hundreds of years.

As a scholar of presidential democracies around the world, I have studied how countries have used electoral colleges. None have been satisfied with the results. And except for the U.S., all have found other ways to choose their leaders.

The origins of the US Electoral College

The Holy Roman Empire was a loose confederation of territories that existed in central Europe from 962 to 1806. The emperor was not chosen by heredity, like most other monarchies. Instead, emperors were chosen by electors, who represented both secular and religious interests.

As of 1356, there were seven electors: Four were hereditary nobles and three were chosen by the Catholic Church. By 1803, the total number of electors had increased to 10. Three years later, the empire fell.

When the Founding Fathers were drafting the U.S. Constitution in 1787, the initial draft proposal called for the “National Executive,” which we now call the president, to be elected by the “National Legislature,” which we now call Congress. However, Virginia delegate George Mason viewed “making the Executive the mere creature of the Legislature as a violation of the fundamental principle of good Government,” and so the idea was rejected.

Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson proposed that the president be elected by popular vote. However, many other delegates were adamant that there be an indirect way of electing the president to provide a buffer against what Thomas Jefferson called “well-meaning, but uninformed people.” Mason, for instance, suggested that allowing voters to pick the president would be akin to “refer(ring) a trial of colours to a blind man.”

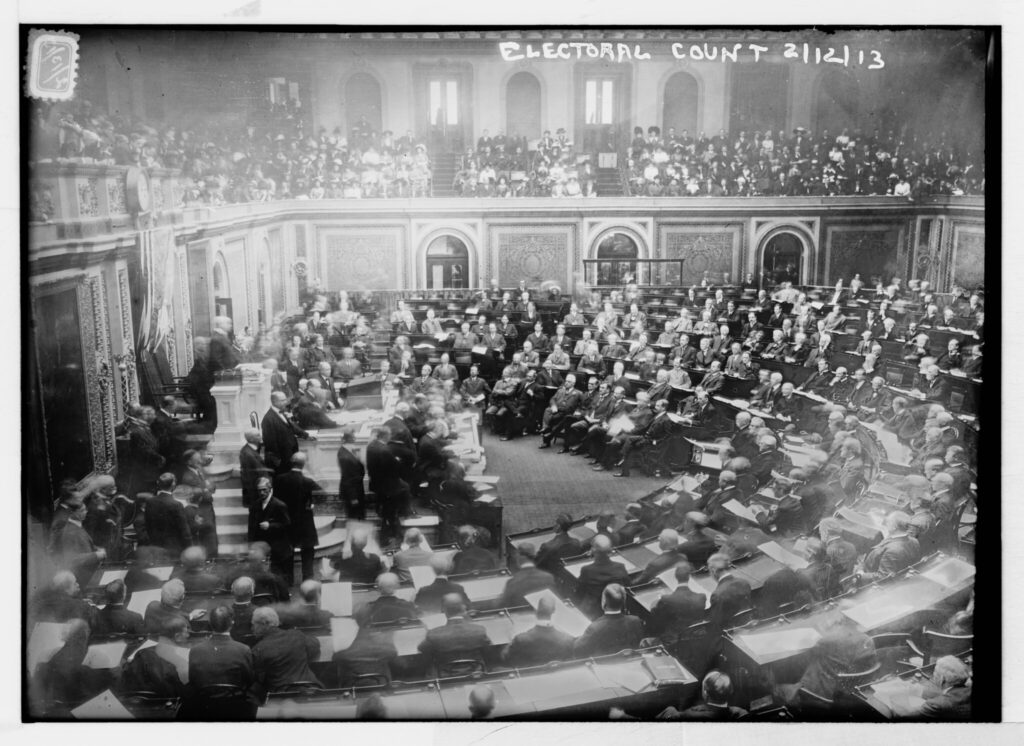

For 21 days, the founders debated how to elect the president, and they held more than 30 separate votes on the topic – more than for any other issue they discussed. Eventually, the complicated solution that they agreed to was an early version of the electoral college system that exists today, a method where neither Congress nor the people directly elect the president. Instead, each state gets a number of electoral votes corresponding to the number of members of the U.S. House and Senate it is apportioned. When the states’ electoral votes are tallied, the candidate with the majority wins.

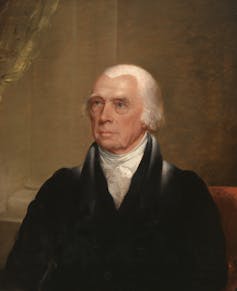

James Madison, who was not fond of the Holy Roman Empire’s use of an electoral college, later recalled that the final decision on how to elect a U.S. president “was produced by fatigue and impatience.”

After just two elections, in 1796 and 1800, problems with this system had become obvious. Chief among them was that electoral votes were cast only for president. The person who got the most electoral votes became president, and the person who came in second place – usually their leading opponent – became vice president. The current process of electing the president and vice president on a single ticket but with separate electoral votes was adopted in 1804 with the passage of the 12th Amendment.

Some other questions about how the electoral college system should work were clarified by federal laws through the years, including in 1887 and 1948.

After the 2020 presidential election exposed additional flaws with the system, Congress further tweaked the process by passing legislation that sought to clarify how electoral votes are counted.

Other electoral colleges

After the U.S. Constitution went into effect, the idea of using an electoral college to indirectly elect a president spread to other republics.

For example, in the Americas, Colombia adopted an electoral college in 1821. Chile adopted one in 1828. Argentina adopted one in 1853.

In Europe, Finland adopted an electoral college to elect its president in 1925, and France adopted an electoral college in 1958.

Over time, however, these countries changed their minds. All of them abandoned their electoral colleges and switched to directly electing their presidents by votes of the people. Colombia did so in 1910, Chile in 1925, France in 1965, Finland in 1994, and Argentina in 1995.

The U.S. is the only democratic presidential system left that still uses an electoral college.

A ‘popular’ alternative?

There is an effort underway in the U.S. to replace the Electoral College. It may not even require amending the Constitution.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, currently agreed to by 17 U.S. states, including small states such as Delaware and big ones such as California, as well as the District of Columbia, is an agreement to award all of their electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate gets the most votes nationwide. It would take effect once enough states sign on that they would represent the 270-vote majority of electoral votes. The current list reaches 209 electoral votes.

A key problem with the interstate compact is that in races with more than two candidates, it could lead to situations where the winner of the election did not get a majority of the popular vote, but rather more than half of all voters chose someone else.

When Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Finland and France got rid of their electoral colleges, they did not replace them with a direct popular vote in which the person with the most votes wins. Instead, they all adopted a version of runoff voting. In those systems, winners are declared only when they receive support from more than half of those who cast ballots.

Notably, neither the U.S. Electoral College nor the interstate compact that seeks to replace it are systems that ensure that presidents are supported by a majority of voters.

This story includes material from a story published on May 20, 2020.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Joshua Holzer is an associate professor of political science at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, where he teaches courses on many different topics, including Chinese politics, European politics, Middle East and North African politics, American foreign policy, and the politics of language.

He has a PhD in political science from the University of Missouri, an MA in teaching from the University of Southern California, a MA in international policy studies from the Monterey Institute of International Studies, and a BA in Asian studies from the University of Denver. He served in the U.S. Army from 2004-2009, during which time he studied Chinese at the Defense Language Institute.