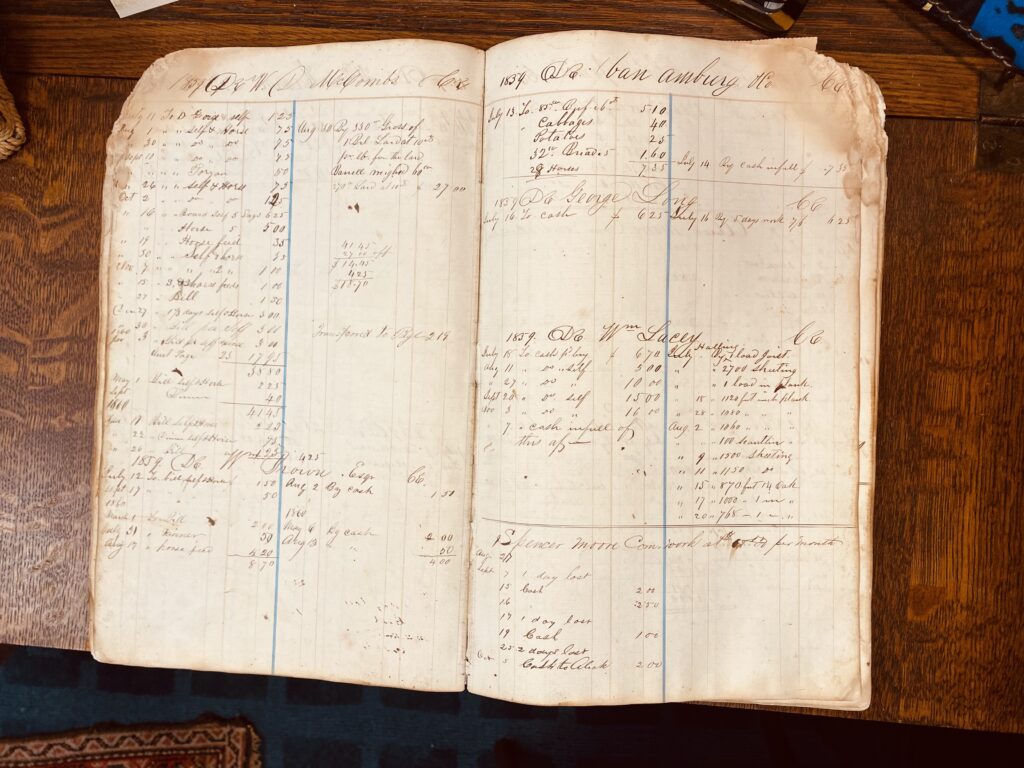

This month’s artifact is a ledger. Feels a bit like deja vu, doesn’t it?

In April, I began a journey to unravel the story of the Ritter House Ledger that was kept at a local boarding house from 1859 through 1860, and I promised to continue that journey this month.

Last month, we got a sense of how the establishment worked, the role it played as a stagecoach stop, and the services it provided. This month, let’s take a look at the people who created Hopkinsville’s Ritter House and those who found bed, board and hearth at this establishment.

A hotelier and keeper of the ledger

What better place to start than with Burwell C. Ritter, the boarding house proprietor and keeper of the ledger. Ritter was born in 1810 in Barren County, Kentucky. Presumably the youngest son of John and Delilah Ritter, Burwell received a limited, rudimentary education in and around Barren and Logan counties. He married in the early 1830s, but I have been unable to find his wife’s name. By 1835, their first child — John P. Ritter — was born. The couple would have seven children before the wife’s death between 1848 and 1850.

The first time I find Burwell Ritter named in the U.S. Census is in 1850. He lived in Logan County as a single father to his seven children, who ranged in age from 2 to 15. Oddly, his occupation was not listed. He was also living next door to Preston Ritter, his older brother, and Preston’s family. Preston worked as a saddler. Two of his young daughters, Flora and Editha, are actually listed twice in the 1850 census — once with their father and once with a Rowlett family in Hart County. Taken nearly two months apart, the young girls were likely visiting family.

It appears that Ritter moved around a bit as a young man.

“The Story of Todd County, Kentucky 1820-1970” (written and compiled by Marion Williams in 1972) lists him as a founding member of the Elkton Christian Church in 1837. In 1848, he was appointed postmaster of Buena Vista Springs northwest of Russellville in Logan County. Ritter also served two terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives — in 1842 and 1850 — both times representing the Logan County area.

Ritter made his home in Hopkinsville in late 1852, when he married Martha Ann Ellison. The daughter of James Ellison, Martha is found in the 1850 census with her father, grandfather and four siblings. She was 28 years old at the time of their marriage; Burwell was 42. The couple had three sons together by 1860.

Ritter purchased the farm and house on today’s Sivley Road from his wife’s father. The house was built by James Ellison in 1843, purchased by Burwell Ritter in 1854, and lived in by his family for decades. Martha lived there at the time of her death in 1891.

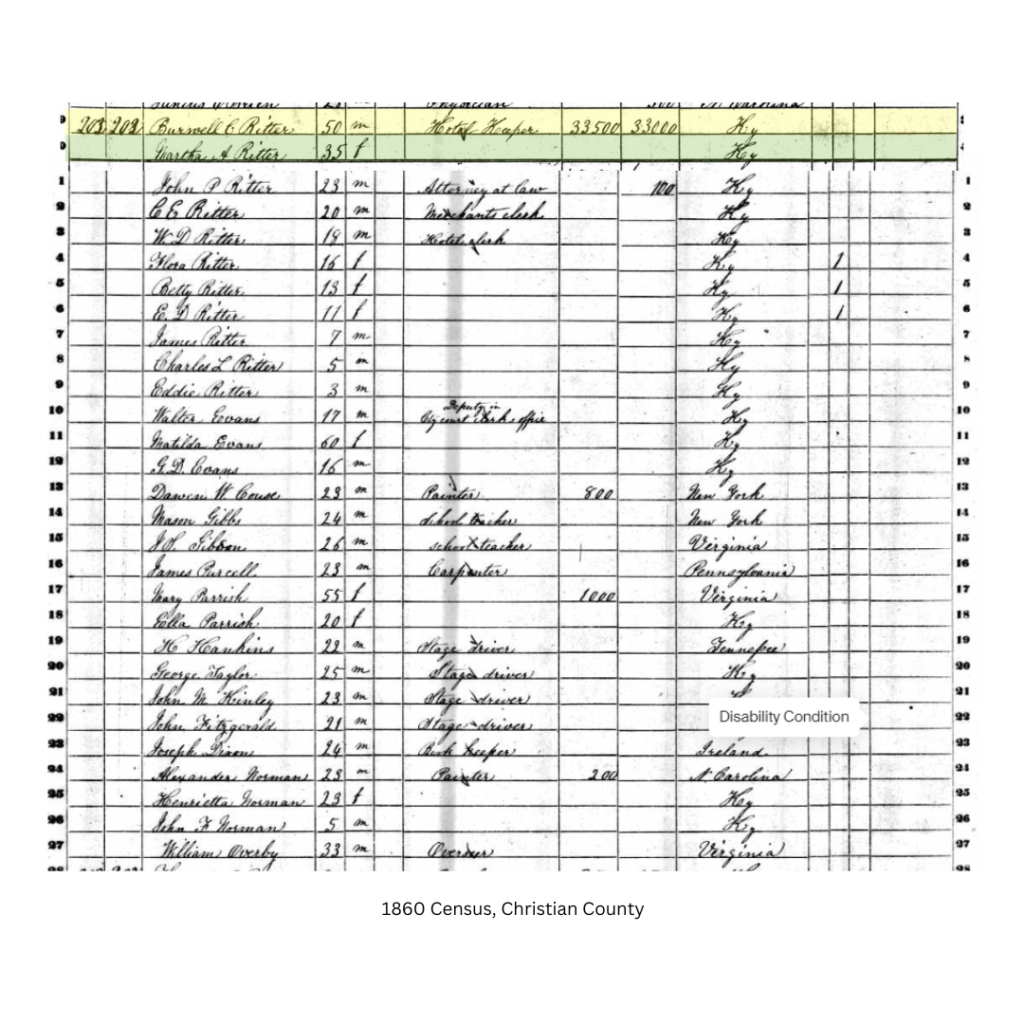

I haven’t been able to figure out exactly when Ritter began his stint as a hotelier, but we know from the ledger that he was in the business by 1859. The 1860 census also lists his occupation as “hotel keeper” with $33,500 valued in his real estate holdings and an additional $33,000 valued in his personal estate. A significant portion of his estate included 38 enslaved people — ranging in age from 5 months to 65 years old. Their names are not provided in the documentation; just their gender and ages. Ritter operated the boarding house and a farm. These people, held in bondage, likely worked at both locations.

Ritter and his family were in residence at the boarding house on July 4, 1860, when the census taker visited. He, Martha, and nine Ritter children are listed along with 18 other people staying at the Ritter House. These boarders included his older sister Matilda Evans and her sons Walter and George, two school teachers (one from New York and one from Pennsylvania), two painters (one with his wife and son), a carpenter, a bookkeeper from Ireland, a mother and her daughter, an overseer, and four stage coach drivers.

Our ledger only shows his business transactions through 1860, so I am not positive as to when he stopped running the boarding house. A real estate transaction between his son John Ritter and James and Mary Ford in 1867 seems to refer to this piece of property — indicating that the Ritter family continued some sort of stake in the establishment until then. But Burwell had moved on to much bigger political pursuits by this time.

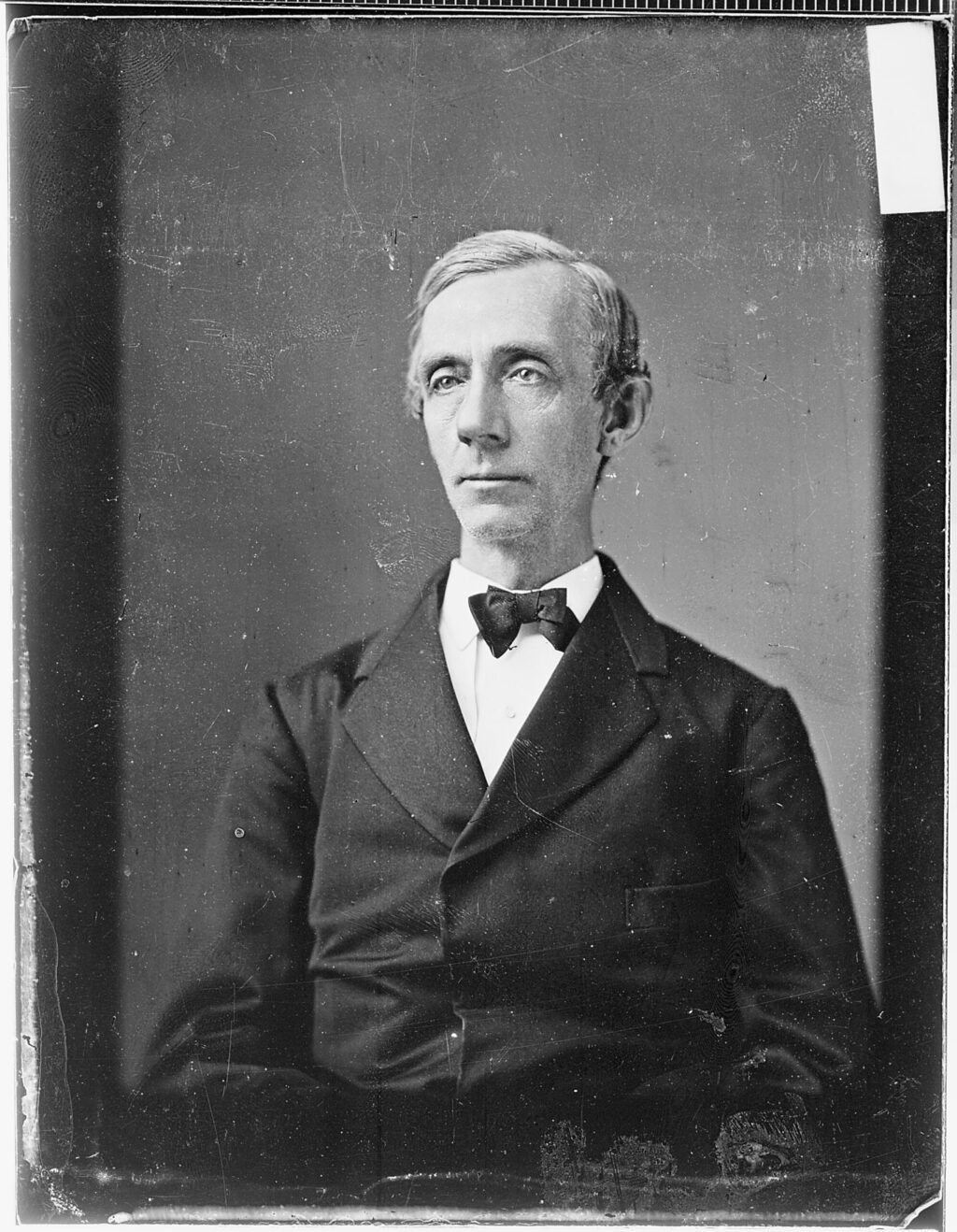

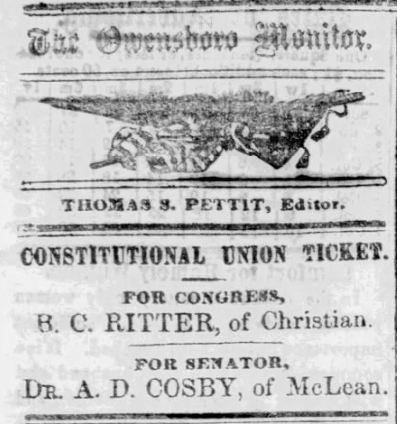

Burwell Ritter ran a successful campaign and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1865. Representing Christian County and the surrounding area, Ritter ran as an anti-abolition, pro-Union Democrat on the Constitutional Union ticket. Arriving in Washington, D.C., in early March 1865, Ritter would have been in office when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15.

This fact tripped me up a bit. A farmer and businessman from Hopkinsville was actively involved in national politics in Washington at this pivotal moment in our collective history? I can hardly wrap my mind around it. Ritter was in Congress for the end of the Civil War — and before the Southern states that had seceded were readmitted for representation. As a member of the 39th Congress, Ritter was present for the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, the Reconstruction Act, the ratification of the 13th Amendment, and the approval of the 14th Amendment to be submitted to states for ratification. (I was unable to find his voting record in Congress, but I doubt he supported all of this legislation.)

He went from running a boarding house on the corner of Ninth and Clay streets in Hopkinsville to participating in some of the most important moments in our nation’s history. Mind. Blown.

Ritter only served one term in Congress after losing his bid for the Democratic nomination in 1867. He attempted to run in opposition to the party’s chosen candidate as an “all-party man.” He lost decisively.

By 1870, Ritter was back on his farm in Christian County with his wife and five of his sons. Also living in his household were his son Barry’s wife and two kids and three African Americans: Anna Ritter, 48, who worked as a domestic servant, Isham Ritter, 9, and Archey Durrett, 55, who worked on the farm.

Burwell C. Ritter died on Oct. 1, 1880, at his daughter Flora’s home. He is buried at Riverside Cemetery in a family plot. Buried just months before in the same plot was his son John P. Ritter who died of tuberculosis on July 5. The son, a well-known and respected local attorney, left behind a wife and two young children. His family moved to Oakland, California, shortly after his death.

Ritter House lodgers

But Ritter’s story is not the only one to be found in this ledger. Here are a few glimpses into some of those who were found at the Ritter House.

Walter Evans

Although his name does not appear in the ledger, Walter Evans, Ritter’s nephew, is listed as a resident of the Ritter House in the 1860 census. At the time, he worked as the deputy in the city court clerk’s office. Evans served as a Captain in the Union Army from 1861-1863, was admitted to the bar, and practiced law in Hopkinsville shortly after the Civil War. He served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention (just as his uncle served as a Democrat in Congress) in 1868, 1872, 1880 and 1884.

After serving a term in the state House of Representatives and in the state Senate, he moved to Louisville in 1874 and continued to practice law. He ran for governor in 1879 and finally ran successful campaigns to the U.S. House of Representatives serving from 1895-1899. President McKinley appointed Evans as a federal judge in the U.S. District Court of Kentucky in 1899, and he served in this role until his death in 1923. He is buried at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

That’s two future US Congressmen living on Ninth Street in 1860! Mind blown again.

Thomas Woodward

This West Point graduate moved from New England to Kentucky and taught school until the outbreak of the Civil War. We find him boarding at the Ritter House in late 1859 and early 1860. His account doesn’t provide much detail other than that he had his laundry done, and he paid in full. He would go on to be one of the first volunteers — and eventually the highest ranking Confederate representing Christian County. He was shot and killed by a Union sniper at the intersection of Ninth & Main streets in 1864.

On the same page of the ledger with Woodward is a short entry for James Brewer. He boarded for four days in November 1859 and accumulated a bill of $6. Brewer would also go on to serve as a Captain in the Confederate Army. He was shot by a Union firing squad in 1864 when he was home on leave in Hopkinsville.

What a bizarre coincidence that these two men with such similar fates would end up on the same page of this ledger.

J.C. Long, B.M. Webster, H.F. Gorin and Charles S. How

These four men were some of the farthest travelers to stay at the Ritter House, and they arrived just a day apart. Long and Webster arrived on Nov. 17, 1859, and were noted as coming from New York. Gorin and How arrived the following day from Philadelphia.

Their accounts were pretty unremarkable: lodging, laundry and hiring a hack. They all paid in cash three days after their arrival — and they didn’t return. But these New England men would have been boarding at the same time as the future Confederate officers mentioned above. I wish I could have been a fly on the wall for those dinner conversations.

Benjamin F., James and David Lotspeich

These men accounted for 14 entries throughout the ledger — the most of any last name in the book. The three men were brothers — all born in Kentucky — and worked as merchants.

Based on how often they are at the Ritter House, I think it’s safe to call them traveling salesmen. In 1850, they are found in the census in both Christian and Trigg counties. Benjamin, the oldest, is listed as a commercial merchant as is his brother James in Christian County, while David shows up in Trigg as a clerk.

They are in and out of the Ritter House through 1859 and 1860; however, brothers Benjamin and James are enumerated in the 1860 census in Jefferson City, Louisiana — just outside of New Orleans. They must have been on a trip because Benjamin is back at the Ritter House for an extensive (and fairly expensive) stay in July. Their accounts often include lodging, meals, laundry services, extra meals for associates and bottles of whiskey.

Benjamin married in 1852 in Christian County. I found him, his wife, and their children in 1870 in Ballard County. James showed up in 1880 in Selma, Alabama — married with two children and working as a cotton broker. David appears to have enlisted in the Confederate Army. He had a family and was selling life insurance in 1870 in Selma, and he died in 1904 in Abilene, Texas.

I told y’all there is enough information in this ledger for a book! Even after two articles, I feel like I have barely scratched the surface of all there is to learn from this one artifact.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.