Meteorologists began warning about severe weather with the potential for tornadoes several days before storms tore across the Southeast and the Central U.S. in late March 2023. At one point, more than 28 million people were under a tornado watch. But pinpointing exactly where a tornado will touch down – like the tornadoes that hit Rolling Fork, Mississippi, on March 24, and towns in Arkansas, Illinois and multiple other states on March 31 – still relies heavily on seeing the storms developing on radar. Chris Nowotarski, an atmospheric scientist, explains why, and how forecast technology is improving.

Meteorologists have gotten a lot better at forecasting the conditions that make tornadoes more likely. But predicting exactly which thunderstorms will produce a tornado and when is harder, and that’s where a lot of severe weather research is focused today.

Often, you’ll have a line of thunderstorms in an environment that looks favorable for tornadoes, and one storm might produce a tornado but the others don’t.

The differences between them could be due to small differences in meteorological variables that aren’t resolved by our current observing networks or computer models. Even changes in the land surface conditions — fields, forested regions or urban environments — could affect whether a tornado forms. These small changes in the storm environment can have large impacts on the processes within storms that can make or break a tornado.

One of the strongest predictors of whether a thunderstorm produces a tornado relates to vertical wind shear, which is how the wind changes direction or speed with height in the atmosphere.

How wind shear interacts with rain-cooled air within storms, which we call “outflow,” and how much precipitation evaporates can influence whether a tornado forms. If you’ve ever been in a thunderstorm, you know that right before it starts to rain, you often get a gust of cold air surging out from the storm. The characteristics of that cold air outflow are important to whether a tornado can form, because tornadoes typically form in that cooler portion of the storm.

How far in advance can you know if a tornado is likely to be large and powerful?

The vast majority of violent tornadoes form from supercells, thunderstorms with a deep rotating updraft, called a “mesocyclone.” Vertical wind shear can enable the midlevels of the storm to rotate, and upward suction from this mesocyclone can intensify the rotation within the storm’s outflow into a tornado.

If you have a supercell on radar and it has strong rotation above the ground, that’s often a precursor to a tornado. Some research suggests that a wider mesocyclone is more likely to create a stronger, longer-lasting tornado than other storms.

Forecasters also look at the storm’s environmental conditions — temperature, humidity and wind shear. Those offer more clues that a storm is likely to produce a significant tornado.

The percentage of tornadoes that trigger a warning has increased over recent decades, due to Doppler radar, improved modeling and better understanding of the storm environment. About 87% of deadly tornadoes from 2003 to 2017 had an advance warning.

The lead time for warnings has also improved. In general, it’s about 10 to 15 minutes now. That’s enough time to get to your basement or, if you’re in a trailer park or outside, to find a safe facility. Not every storm will have that much lead time, so it’s important to get to shelter fast.

What are researchers discovering today that can help protect lives?

If you think back to the movie “Twister,” in the early 1990s we were starting to do more field work on tornadoes. We were taking radar out in trucks and driving vehicles with roof-mounted instruments into storms. That’s when we really started to appreciate what we call the storm-scale processes — the conditions inside the storm itself, how variations in temperature and humidity in outflow can influence the potential for tornadoes.

Scientists can’t launch a weather balloon or send instruments into every storm, though. So, we also use computers to model storms to understand what’s happening inside. Often, we’ll run several models, referred to as ensembles. For instance, if nine out of 10 models produce a tornado, we know there’s a good chance the storm will produce tornadoes.

The National Severe Storms Laboratory has recently been experimenting with tornado warnings based on these models, called Warn-on-Forecast, to increase the lead time for tornado warnings.

There are a lot of other areas of research. For example, to better understand how storms form, I do a lot of idealized computer modeling. For that, I use a model with a simplified storm environment and make small changes to the environment to see how that changes the physics within the storm itself.

There are also new tools in storm chasing. There’s been an explosion in the use of drones — scientists are putting sensors into unmanned aerial vehicles and flying them close to and sometimes into the storm.

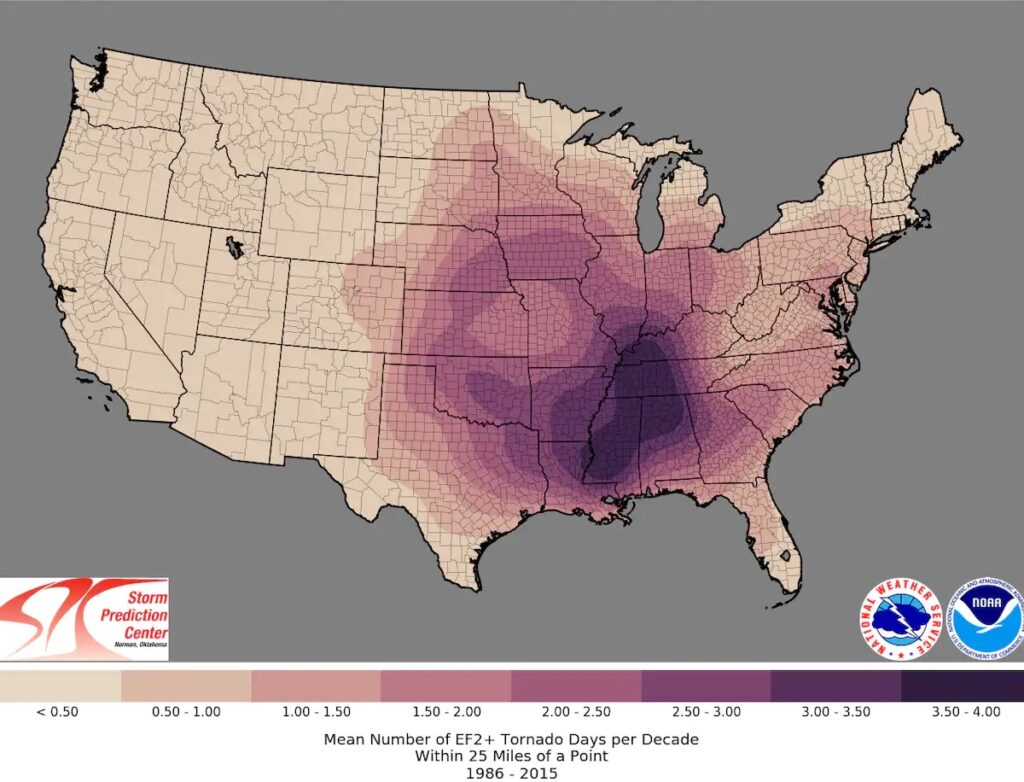

The focus of tornado research has also shifted from the Great Plains — the traditional “tornado alley” — to the Southeast.

What’s different about tornadoes in the Southeast?

In the Southeast there are some different influences on storms compared with the Great Plains. The Southeast has more trees and more varied terrain, and also more moisture in the atmosphere because it’s close to the Gulf of Mexico. There tend to be more fatalities in the Southeast, too, because more tornadoes form at night.

We tend to see more tornadoes in the Southeast that are in lines of thunderstorms called “quasi-linear convective systems.” The processes that lead to tornadoes in these storms can be different, and scientists are learning more about that.

Some research has also suggested the start of a climatological shift in tornadoes toward the Southeast. It can be difficult to disentangle an increase in storms from better technology spotting more tornadoes, though. So, more research is needed.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chris Nowotarski is associate professor of Atmospheric Science at Texas A&M University. His research is geared toward developing a better understanding of the structure and dynamics of convective storms in midlatitudes with the ultimate goal of improving prediction of such events and their attendant hazards.