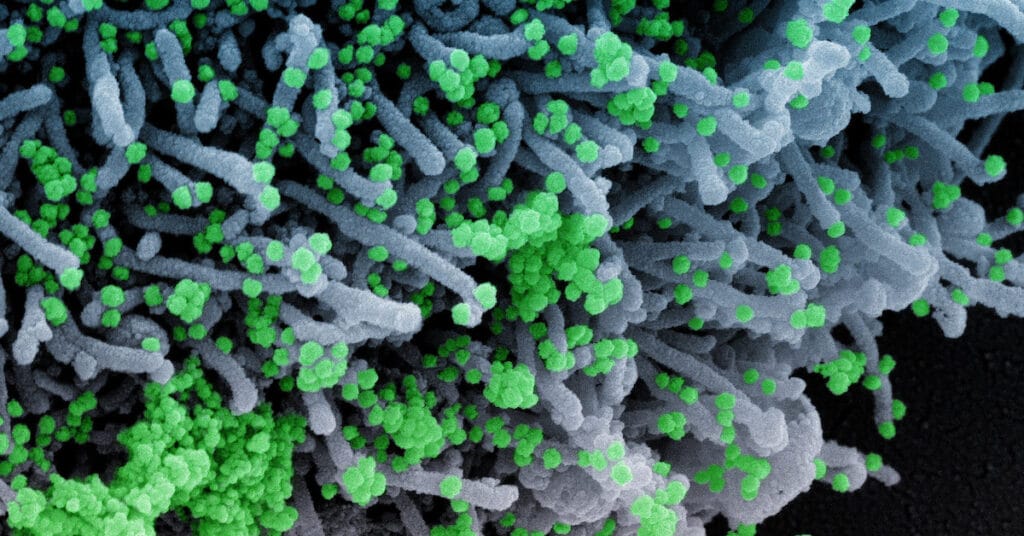

A new omicron subvariant of the virus that causes COVID-19, BA.2, is quickly becoming the predominant source of infections amid rising cases around the world. Immunologists Prakash Nagarkatti and Mitzi Nagarkatti of the University of South Carolina explain what makes it different from previous variants, whether there will be another surge in the U.S. and how best to protect yourself.

What is BA.2, and how is it related to omicron?

BA.2 is the latest subvariant of omicron, the dominant strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. While the origin of BA.2 is still unclear, it has quickly become the dominant strain in many countries, including India, Denmark and South Africa. It is continuing to spread in Europe, Asia and many parts of the world.

The omicron variant, officially known as B.1.1.529, of SARS-CoV-2 has three main subvariants in its lineage: BA.1, BA.2 and BA.3. The earliest omicron subvariant to be detected, BA.1, was first reported in November 2021 in South Africa. While scientists believe that all the subvariants may have emerged around the same time, BA.1 was predominantly responsible for the winter surge of infections in the Northern Hemisphere in 2021.

The first omicron subvariant, BA.1, is unique in the number of alterations it has compared to the original version of the virus – it has over 30 mutations in the spike protein that helps it enter cells. Spike protein mutations are of high concern to scientists and public health officials because they affect how infectious a particular variant is and whether it is able to escape the protective antibodies that the body produces after vaccination or a prior COVID-19 infection.

BA.2 has eight unique mutations not found in BA.1, and lacks 13 mutations that BA.1 does have. BA.2 does, however, share around 30 mutations with BA.1. Because of its relative genetic similarity, it is considered a subvariant of omicron as opposed to a completely new variant.

Why is it called a ‘stealth’ variant?

Some scientists have called BA.2 a “stealth” variant because, unlike the BA.1 variant, it lacks a particular genetic signature that distinguishes it from the delta variant.

While standard PCR tests are still able to detect the BA.2 variant, they might not be able to tell it apart from the delta variant.

Is it more infectious and lethal than other variants?

BA.2 is considered to be more transmissible but not more virulent than BA.1. This means that while BA.2 can spread faster than BA.1, it might not make people sicker.

It is worth noting that while BA.1 has dominated case numbers around the world, it causes less severe disease compared to the delta variant. Recent studies from the U.K. and Denmark suggest that BA.2 may pose a similar risk of hospitalization as BA.1.

Does previous infection with BA.1 provide protection against BA.2?

Yes! A recent study suggested that people previously infected with the original BA.1 subvariant have robust protection against BA.2.

Because BA.1 caused widespread infections across the world, it is likely that a significant percentage of the population has protective immunity against BA.2. This is why some scientists predict that BA.2 will be less likely to cause another major wave

However, while the natural immunity gained after COVID-19 infection may provide strong protection against reinfection from earlier variants, it weakens against omicron.

How effective are vaccines against BA.2?

A recent preliminary study that has not yet been peer reviewed of over 1 million individuals in Qatar suggests that two doses of either the Pfizer–BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines protect against symptomatic infection from BA.1 and BA.2 for several months before waning to around 10%. A booster shot, however, was able to elevate protection again close to original levels.

Importantly, both vaccines were 70% to 80% effective at preventing hospitalization or death, and this effectiveness increased to over 90% after a booster dose.

How worried does the US need to be about BA.2?

The rise in BA.2 in certain parts of the world is most likely due to a combination of its higher transmissibility, people’s waning immunity and relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions.

CDC data suggests that BA.2 cases are rising steadily, making up 23% of all cases in the U.S. as of early March. Scientists are still debating whether BA.2 will cause another surge in the U.S.

Though there may be an uptick of BA.2 infections in the coming months, protective immunity from vaccination or previous infection provides defense against severe disease. This may make it less likely that BA.2 will cause a significant increase in hospitalization and deaths. The U.S., however, lags behind other countries when it comes to vaccination, and falls even further behind on boosters.

Whether there will be another devastating surge depends on how many people are vaccinated or have been previously infected with BA.1. It’s safer to generate immunity from a vaccine, however, than from getting an infection. Getting vaccinated and boosted and taking precautions like wearing an N95 mask and social distancing are the best ways to protect yourself from BA.2 and other variants.![]()

Prakash Nagarkatti is a Professor of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology at University of South Carolina and Mitzi Nagarkatti is a Professor of Pathology of Microbiology and Immunology at University of South Carolina. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dr. Mitzi Nagarkatti is SmartState Endowed Chair of Center for Cancer Drug Discovery as well as Carolina Distinguished Professor and Chair of the Dept. of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology at the School of Medicine (SOM), University of South Carolina (UofSC). In 2005, Dr. Nagarkatti moved from the Medical College of Virginia where she was a Professor in the Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology as well as directed the Immune Mechanisms Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Massey Cancer Center.

Dr. Nagarkatti’s research is broad-based and encompasses Inflammation, Autoimmunity, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy, and Immunotoxicology. Dr. Nagarkatti has been the recipient of >$70million in extramural funding as Principal Investigator (P.I.)/Co-P.I. to support the research in her lab since moving to UofSC. She is currently theP.I./on 3 National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grants. She also serves as the Co-P.I. of yet another Center Grant for $6million from National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) to study the epigenetic mechanisms underlying the role of plant products in treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, which was renewed for an additional 5 years for $8million. In addition, Dr. Nagarkatti is also a Co-P.I. on a 5-year COBRE grant on Dietary Supplements and Inflammation for $10million which was a renewal of a previous 5-year grant for $10million, aimed at recruiting and mentoring junior faculty. Dr. Nagarkatti’s research has been continuously funded by agencies including the NIH, VA, US Army, American Cancer Society, NSF/EPA as well as other private foundations.

Dr. Nagarkatti is an American Association for Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) Fellow as well as Fellow of the Academy of Toxicological Sciences. Dr. Nagarkatti was appointed to the prestigious National Toxicology Program (NTP) Board of Scientific Counselors. Dr. Nagarkatti has been the recipient of numerous awards such as the Pfizer Award, UofSC Breakthrough Leadership Award, Diversity and Inclusion Leadership Award, etc. Dr. Nagarkatti has trained several undergraduate, graduate, medical and veterinary students, postdoctoral fellows and junior faculty. She has published ~300 scientific papers in high-impact journals and presented ~450 research abstracts at international, national and regional meetings. She has been an invited speaker and has chaired scientific sessions at national and international meetings. Dr. Nagarkatti has served as a reviewer for grant proposals for funding agencies such as National Institutes of Health (NIH), American Cancer Society (ACS), Dept. of Defense (DOD), etc. She is currently a regular member of NIH SIEE Study Section.