The world of stage and screen is mourning the death of prolific actor Ned Beatty, who died June 13 at age 83 at his Burbank, California, home. Half a country away in Appalachia, people are sad to learn of his passing, too. Though Ned Beatty’s first appearance in the national cinematic spotlight included a controversial and horrific rape scene by a Georgia backwoodsman in “Deliverance,” he was a true supporter and believer in Appalachia.

I first became acquainted with Ned Beatty when we met on the film set—actually, it was at the chuck wagon—for the movie “Kentucky Woman.” Ned was cast as a disabled miner with black lung who was the father of a woman coal miner and single mother, played by actress Cheryl Ladd. I stood in the chow line on the first day of the film shoot. After picking out my food, I chose an empty table across the way and went for a glass of lemonade. As I sat back down, I noticed a stocky, genial-looking character with a familiar face headed for the food wagon. It was Ned Beatty wearing his signature floppy hat and dressed in baggy khaki pants and a long-sleeve shirt. A hush fell over the other two tables full of young actors across from me. In their eagerness to fraternize, they had left no place for anyone else to sit. When Ned got his lunch tray, he sauntered over to my table where I sat alone.

“May I join you there, partner?” he said.

“Why, sure,” I replied. My heart hammered slightly.

“You can call me Ned,” he said as he offered his hand.

I reached to shake it and said, “I’m Jack. I’m playing ‘Pete’ the coal miner.”

The other tables looked on and then continued with their chatter.

“One thing about these remote shots,” Ned said, “They always have good grub.”

As we ate, we got to know each other. I told him of my work at Appalshop, a media arts center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, as an audio engineer, storyteller and aspiring filmmaker.

“My family is from Harlan County,” he said. “My mother grew up there and I still have cousins there. I acted at Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Virginia, for several years. I was in a troupe that took plays to schools around Southwest Virginia, Eastern Kentucky and part of North Carolina.”

“What a coincidence,” I said, “Barter came to my high school and put on a couple of plays with Jim Mitchum back in 1960. It was the first real theater I ever saw.”

“Yes, that was us. We presented ‘Rapunzel,’ ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ and several other short plays, had a big time on that little tour.”

We talked on and I told Ned about Roadside Theater and how we focused our work on Southern Mountain culture. Our first original play, “Red Fox/ Second Hangin’,” was to begin a three-week summer run at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival in Anniston, Alabama.

His ears perked up. “Oh,” he said, “I’m shooting a movie with Burt Reynolds not far from there, just over the Georgia line, called ‘Stroker Ace.’ I’ll have to come by and see your play.”

As we finished up the meal, he wrote down his personal phone number and his Hollywood Hills home address. “Keep in touch,” he said.

Through our lunchtime encounter, Ned and I formed a tight friendship that would last from that day in 1982 until his recent death.

My meeting with Ned proved fortuitous, as he soon became an enthusiastic supporter of Appalshop. While acting in “Stroker Ace,” he made the trip to the Alabama Shakespeare Festival to see Roadside’s performance. Afterword he called me at Appalshop and told me he was impressed with ‘Red Fox/Second Hangin’.” But it was a documentary film that would soon draw him closer to the Appalshop family.

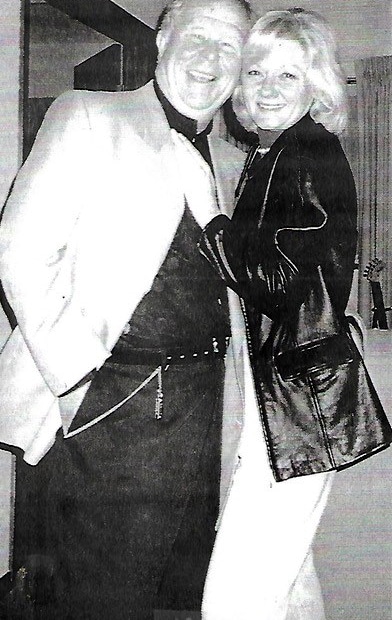

In 1983 Appalshop released “Strangers and Kin: A History of the Hillbilly Image.” The film’s March 1984 premiere also served as a fundraiser, so we invited Ned as the guest speaker. My wife Sharon and I picked him up at Tri-Cities airport. Ned was quite friendly and open. He was also a man of faith. After we had supper at the Martha Washington Inn in Abingdon, Virginia, he asked for quiet time while he meditated and prayed silently during the drive back to Whitesburg, Kentucky.

In the opening scene of the documentary, director and editor Herb E. Smith chose a clip of one of the early scenes in “Deliverance.” On the soundtrack we hear the now famous instrumental banjo tune “Dueling Banjos.” In the background Ned’s character Bobby walks up to Ed (Jon Voight) standing outside a country grocery store and gas station. Bobby says, “Talk about genetic deficiencies.” Ed answers, “Isn’t that pitiful?” The film’s negative stereotypical comment on mountain people fit a longtime traditional pattern.

Herbie insisted it was important for Ned to view the hour-long movie in our theater before the coming premiere and festivities. Herbie projected the film for Ned in our darkened theater. At the end of the film the lights came up and Ned sat crying. An awkward moment for us. Herbie asked Ned if he was disappointed with the “Deliverance” clip at the head of the movie. Ned replied, “Oh no, Herbie, it wasn’t that.” He said it was all the persistent negative hillbilly images documented throughout history that got to him emotionally. That and the movie’s powerful ending scene featuring North Carolina master storyteller and mystic Ray Hicks.

Though he had lived in Hollywood for years, Ned never forgot that he was a native son of Kentucky. As local fans flocked to Appalshop to meet Ned, he spoke as if he’d found old members of the family. The premiere’s fundraisers held in Whitesburg and Lexington proved a tremendous success. After the screening he gamely faced some of the audience criticism against the horrific stereotypes “Deliverance” had wrought.

Though Ned was well known by the 1970s for his work in Hollywood, his first love had been music. Ned’s early life in a suburb of Louisville included singing in a barbershop quartet, a gospel group, and his church choir. He had considered the ministry. Transylvania College awarded him a choral scholarship, but he told me that he dropped out after the first semester. College life had proven it was not for him.

Later that spring he tried out as a singer for “Wilderness Road,” the outdoor symphonic drama opening at the newly constructed Indian Fort Theater in Berea, Kentucky, written by the renowned Paul Green. Being short of actors, the director soon put a rifle in singing Ned’s hands and said, “Here, you’re going to act.” Ned told me, “It was the end of my formal education and the beginning of my real education.” When the season closed, he returned home and got a job as a supermarket butcher’s assistant. He also was cast in several local plays around Louisville, including the budding Actor’s Theater, where he appeared in several productions.

The next spring he returned to Indian Fort for another season and then made haste to the Barter, an Actor’s Equity theater in Abingdon, Virginia. There he began his successful thespian career, performing in over 30 productions in a 10-year period. Before one of those plays, his first wife, Walta, gave birth five minutes before curtain time. She had three of eight children he shared with three of his four wives.

In 1968 Ned moved to the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., building a name for himself in the theater world. He later said to me, “My university was the theater, Jack. Barter was my undergrad and Arena, my graduate work.” While he worked at Arena, he took a trip to New York City accompanied by fellow Arena actor Ronny Cox, auditioning with John Boorman for “Deliverance,” which changed his life and added a chapter in American cinematic history.

After the success of “Deliverance,” Ned later joked, “It’s been all downhill, the whole film career.” Yet four years after that breakthrough film, he would receive an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor as Arthur Jenson, the media executive in “Network” who tolerates no meddling in the primordial swamp of capitalism.

In 1985 I moved to Ohio to attend graduate school and later got a job with the Ohio Arts Council. In 1988 I received a call from Andy Garrison, an Appalshop filmmaker. Andy had developed a film script based on the short story “Fat Monroe” from Gurney Norman’s acclaimed book Kinfolks. Andy thought Ned would be perfect for the lead role. I called Ned on Andy’s behalf. Indeed, he was interested, and Andy convinced him. Production on the nine-day shoot began in the spring of 1989, staged around Letcher County. I served as Ned’s assistant. The short film starred three players: Ned, the cantankerous Fat Monroe; 11-year-old William Johnson as Wilgus Collier; and Jerry Johnson (no relation) as coal miner and father to Wilgus. The movie later opened at the prestigious New York Film Festival where New York Times film critic Vincent Canby gave it a rave review, labeling it “…a pint-sized classic.”

In the spring of 1989, 1,400 miners went out on strike against Pittston Coal. A picket line was set up at the Dickenson County, Virginia, Moss #3 coal preparation plant. With the filming of “Fat Monroe” wrapped, Ned insisted on taking a trip to the strike at nearby Carbo, Virginia. That day 62 protesters had been cuffed and dragged off by Virginia state troopers for their passive sit-down demonstrations to block coal trucks coming into the plant to unload coal.

Dressed in camouflage, the uniform of the striking miners, Ned gave a speech that fired the crowd up. Himself a member of the Screen Actors Guild, Ned stated there had been recent efforts at union-busting according to the Harrisonburg (Va.) Daily News. “We’ve got to put a stop to it. … I think every employer in this country, if he has a union to deal with, wants to get rid of it,” he said. “The person who taught them this is Ronald Reagan when he fired the air traffic controllers.” After lending support to the striking miners, he made a generous donation to the UMWA’s strike fund.

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up for Hoptown Chronicle’s newsletters

Aside from politics, news of the upcoming Memorial Day weekend softball game—a tradition among the Appalshop family—piqued Ned’s interest. One reason Ned wanted to visit the annual party, known to fellow revelers as the Inter-Mountain All Star No Star Spiritual Convention Chicken Pluck and Round-Robin Softball Memorial Tournament, was to get some time to visit with one of his oldest sons, Charlie. So, after wrapping up the “Fat Monroe” shoot and time on the picket line, he met Charlie in Tennessee for the softball tournament at Cove Lake where the rules include you can’t strike out and you have to play under the influence of a foreign substance. Like many before him from bygone games, Charlie stepped to the plate and missed a good 15 or 20 pitches in a row. Slow pitches. Easily hit pitches. Finally, Ned jumped up and marched to the batter’s box, took the bat from him, smacked the next pitch and told Charlie, “Run!”

In the early 1990’s Sharon and I visited Ned at his home, which sat just below the famous Hollywood sign in Beverly Hills on North Beachwood Drive. While she did research at the University of Southern California’s Warner Brothers archive, Ned and I had an afternoon of music, he on string bass and I on his small Martin guitar. We sang up a small cyclone while his young daughter, Dorothy, watched and then went to play. Ned rolled out the red carpet and cooked us a tasty supper when Sharon returned. At the time he was building a getaway at Camp Nelson in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He wanted to take me there to show me his endeavors, but alas, our time in California ran out.

As Ned’s career continued, he juggled projects in television, film and theater simultaneously, once again proving Daily Variety’s pronouncement that he was “the busiest actor in Hollywood.” In 1996 he took the role of Cap’n Andy in the Hal Prince production of the legendary musical “Show Boat,” which successfully toured Canada and the U.S. for a little over a year. Ned sparkled in the many reviews of the show.

Still he found time to generously support projects in Appalachia. In May 1997 the Athens International Film and Video Festival at Ohio University brought Ned to Athens, Ohio, in honoring the 25th anniversary of “Deliverance.” By now I lived in Athens and taught at the Ohio University School of Film. When Ned arrived at my home, we immediately set about to build a washtub bass. I drilled a hole in the middle of the brand-new tub’s bottom, and he strung and knotted a piece of twine through it. He found a long stout stick from the nearby woods to use as the bass’s neck. After completing the fabrication of the washtub bass and fine-tuning it, we began to practice. As I sang “Payday,” a song I’d learned from legendary country blues guitarist Mississippi John Hurt’s recording, it triggered a memory for Ned.

On tour in the 1960s, Ned was singing in his St. Matthews church group when he got to meet John Hurt. The problem was that Hurt, like many old-timers late in life, was only playing church music. Ned asked around and learned that Mr. Hurt was known to take an occasional nip, and if he had enough nips, he might be convinced to play the blues. Ned told of politely chatting with Hurt as he played Christian music and discreetly offering him whiskey in a coffee cup, refilling both of their cups each time they ran low. Ned said he heard the first bent string blues note come out of Mississippi John Hurt’s guitar just before he, Ned, fell asleep on the couch. He was told he missed a great show.

Our practice at my home finished, we journeyed into town for some supper, taking our instruments with us. Following a fine meal at a local restaurant, we brought in our instruments, mounted the small elevated stage and performed some country blues in honor of Mr. Hurt, as well as Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man” and “Bright Lights, Big City.” Ned’s enthusiastic approach to playing the homemade gutbucket bass was a crowd pleaser.

A couple of years later, after the success of anniversary screening of “Deliverance,” Ned was invited back to the festival with the recent release of the independent movie “Spring Forward.” He fielded questions in the packed house after the screening and visited Ohio University classes, giving film and theater students advice. Both of his visits to Athens showed Ned’s generosity to those of us living in Appalachia. He would accept no artist honorarium for his work, doing it as a favor to me and the festival. He even donated the cost of his first-class air fare from L.A.

In 2005 I began production of an anthology, “Music of Coal: Mining Songs from the Appalachian Coalfields.” Knowing Ned’s love of singing, I asked if he would sing the Merle Travis song “Sixteen Tons” for the project. I had my friend Dub Cornett produce the track in a Hollywood studio. I asked that the studio send me a bill, but before I knew it, Ned had picked up all the costs for the recording time and backup studio musician fees. Ronny Cox also participated.

After we met in 1982, Ned Beatty always considered me the brother he never had. On my birthday in 2017 he and his wife Sandy called up and sang “Happy Birthday.” We chatted for the last time. Alzheimer’s was slowly taking away his gifts. I kept up with him through Sandy, calling her to check in. The Monday after his passing we talked. She informed me Ned had donated his body to science. How appropriate, I thought. After decades of giving full measure to his audiences, he was now giving his ultimate gift to humanity.

Later I came across the last photo I took of Ned. It was 2003 when he was playing the acclaimed role of Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” on Broadway—a masterful performance that netted him the Drama Desk Award. He and Sandy had invited Sharon and me up for the long Thanksgiving weekend. The morning just before we left for our flight back home, I snapped a photo of Ned in his night shirt, tenderly holding their tiny kitten, Matilda. They had rescued the abandoned animal and nursed her daily with an eye dropper. Nurturing came easy and natural to Ned and Sandy.

Jack Wright is a filmmaker, audio producer, musician, and actor who lives in southeast Ohio. He is retired from the faculty of the Ohio University School of Film.

Jack Wright is a filmmaker, audio producer, musician, and actor who lives in southeast Ohio. He is retired from the faculty of the Ohio University School of Film.