Though homelessness is usually considered an urban problem, it’s a growing problem in rural areas. One in three rural Americans say homelessness is a problem in their community. Mary Meehan reports for Ohio Valley ReSource, a public-radio partnership.

“As the Ohio Valley’s profound addiction epidemic stresses the social safety net, advocates say more rural people are at risk of becoming homeless. But the scattered and hidden nature of homelessness in rural places makes it an especially hard problem to measure and address.”

Homeless rural people are more likely to be unsheltered, or sleeping outside or in tents, as opposed to sleeping on someone’s couch or in a homeless shelter, Meehan reports. A 2018 Department of Housing and Urban Development report found that rural homeless are more likely to be unsheltered than urban homeless people.

The camps in which unsheltered people often live in can pose serious health threats, since residents rarely have access to clean water and often store and dispose of human waste in unsanitary ways. “Conditions like those contribute to disease, such as the Hepatitis A outbreak which has claimed 58 lives in Kentucky so far and sickened approximately 5,000 people, many of them homeless,” Meehan reports. Unsheltered homeless people also risk dying of hypothermia in the winter.

Because rural homeless camps tend to be hidden, many rural officials aren’t aware there are homeless people in their communities, Meehan writes. In rural communities that are aware of their homeless population, churches often provide support, but often don’t have wherewithal to solve the problem.

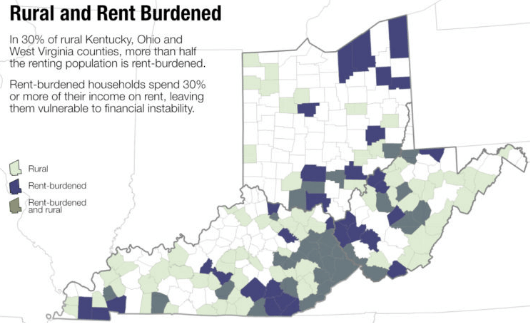

Many rural residents of the Ohio Valley states are at risk of becoming homeless; more than half of the renting population is rent-burdened, which means they spend more than 30% of their income on rent. That leaves them with limited means to deal with unexpected financial problems like a broken-down car or a job loss. “A lot of people in the world don’t realize it, but they are one paycheck away from being out here with us,” Charles “Country” Bowers told Meehan. Bowers lived in a homeless camp in the rural area of Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky, for a long time and said he has long struggled with alcoholism.

Ginny Ramsey, who runs a shelter called the Catholic Action Center in Lexington, told Meehan that many of the chronically unsheltered homeless are dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder, mental illness, and/or addiction that make them reluctant to be around others. The opioid epidemic is making the problem worse, she said: “The safety nets that have been in place, they are leaking, they have always been leaking. Now, they are getting shredded.”

Homeless people may have a hard time getting back into housing due to criminal records, and much of the cheapest housing is in unsafe neighborhoods where drug and alcohol use are prevalent, Meehan reports. And rural areas may not have easy access to addiction treatment.

(This report first ran on The Rural Blog, a digest about rural America published by the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the University of Kentucky.)

The Rural Blog is a publication of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues based at the University of Kentucky.